Jeremy Ayers (1948–2016) was a central figure bridging Southern culture with international avant-garde circles. Early in his career, under the name Sylva Thinn, he appeared in Andy Warhol’s films and became part of the Factory milieu in 1970s New York. Returning to Athens, Georgia, Ayers became an influential writer, musician, performer, and photographer. He was closely tied to the B-52s, R.E.M., and the wider community of artists and musicians that shaped the city into a creative capital.

Ayers’s artistic practice defied a single medium. His work encompassed performance, photography, and collaborative projects that embodied both generosity of spirit and conceptual rigor. His influence continues to be felt not only in music history but also in contemporary art, where his legacy serves as a point of connection between local practice and international discourse.

Psychological Landscapes

Photography, Interior States, and the Construction of Meaning

Psychological Landscapes brings together a body of photographic work produced in the 1990s and later revisited through exhibition and critical writing in the early 2020s. The project examines how psychological states, memory, and embodied experience shape perception, approaching photography not as a record of external reality but as a space where inner and outer worlds intersect.

Made during a period of intense experimentation within photographic and cinematic practices, the works resist the conventions of documentary clarity that dominated much late-twentieth-century image culture. Rather than functioning as isolated images, they operate as sequences in which meaning unfolds gradually through repetition, variation, and return. The photographs encourage sustained attention, withholding narrative closure in favor of psychological resonance.

Conceptual Orientation

The series emerged from an engagement with psychological structures and the challenge of visualizing internal experience without illustration. Drawing loosely from depth psychology and phenomenological thinking prevalent in late twentieth-century cultural discourse, the work considers how photography might register unconscious or pre-verbal states—sensations and emotions that are felt rather than articulated.

Landscape, in this context, is not geographic. It is psychological: shaped by memory, gesture, and perception. Figures and environments are interdependent, with surrounding space functioning as an extension of inner life rather than a neutral setting. Ambiguity is central to the work, allowing images to remain open to interpretation rather than directing the viewer toward fixed meaning.

Form, Sequencing, and Process

Formally, Psychological Landscapes reflects an engagement with both still photography and cinematic logic characteristic of the 1990s, when boundaries between media were increasingly porous. Cropping, pacing, and sequencing play a central role, disrupting linear narrative and emphasizing duration. Images are conceived in relation to one another, with subtle shifts in posture, framing, and atmosphere carrying psychological weight.

The work favors restraint over spectacle. Repetition functions as a structural device, mirroring the rhythms of thought and memory. This approach positions the photograph not as a conclusive statement but as an evolving site of inquiry—one attentive to presence, vulnerability, and lived time.

Critical Context

Critical writing surrounding the work has emphasized its resistance to symbolic closure and its reliance on psychological openness. Rather than offering definitive interpretations, the photographs create conditions for engagement in which meaning remains provisional and responsive to the viewer. This refusal of resolution situates the work within broader late-twentieth-century conversations about subjectivity, interiority, and the limits of photographic representation.

Seen in this light, Psychological Landscapes aligns with practices that questioned documentary authority and explored photography’s capacity to hold emotional and psychological complexity without reducing it to narrative or explanation.

Exhibition and Institutional Placement

Although produced in the 1990s, Psychological Landscapes has continued to find relevance in later exhibition contexts that foreground slow looking and thematic continuity. Its modular structure allows for flexible installation, from tightly sequenced presentations to more open configurations that emphasize dialogue between images.

The work is particularly suited to institutional programs addressing memory, embodiment, identity, and psychological experience, as well as exhibitions examining late-twentieth-century shifts in photographic practice. It can function as a focused solo presentation or as part of a broader thematic exhibition concerned with interiority, perception, and the ethics of representation.

Continuing Relevance

In contrast to the accelerated image economies that followed its production, Psychological Landscapes insists on duration and attentiveness. The work asks viewers to remain with uncertainty and to approach images as encounters rather than consumable moments.

By resisting spectacle and narrative closure, the series continues to offer a rigorous framework for considering how photography can register internal states, lived time, and psychological presence—demonstrating the lasting relevance of work rooted in sustained inquiry rather than immediacy.

PSYCHOLOGICAL LANDSCAPES REVISITED

Jeremy Ayers was highly influential for me as a photographer when I moved to Athens, GA, in the 1980s. We were never extremely close, but he had a mysterious and powerful creativity that drew me into many questions about art. We started having deeper conversations in 1991 on College Square in Athens when I started delving more into medium-format photography. I bought a Mamiya 6 and then an RZ-67, and Jeremy was one of my first subjects in experiments with portraits. In 1994, I felt I needed a change from Athens and asked him for advice. He said,'. "Leave town for a few years, and you will find things are much better when you return." I left for nine years, worked at my first gallery job, and started exhibiting many of the images and ideas I was working on in Athens. Jeremy's words felt prophetic when I returned in 2003 for a one-person show at Paul Thomas's X-ray Cafe. Athens received the work well. The Athens Banner-Herald covered the show with a full-page article, and Flagpole published a video still on the cover during the exhibition. Jeremy confided to me that he had made paintings from my photographs, and we corresponded until he passed in 2016. He is such an inspiration to many people in Athens and worldwide.

In our conversations from 2003 onward, we discussed images and stories. I was particularly intrigued in the early 90s by a circular hologram that Jeremy carried, which he would flash at others with similar holograms, and he would run out of the building where I had a studio. Some of the works in 2003 were inspired by my perceptions of Jeremy with his hologram. The 2003 exhibition with some additional material is linked here. Missing Jeremy dearly.

John Lee Matney, October 24, 2023

Psychological Landscapes

Reprinted by permission of the Athens Banner-Herald with additional material

By Melissa Link

Correspondent

Often calling to mind stills from 1920s-era cinema, Matney's photos capture the figure in various states of contortion and relaxation, creating an illusion of continued motion

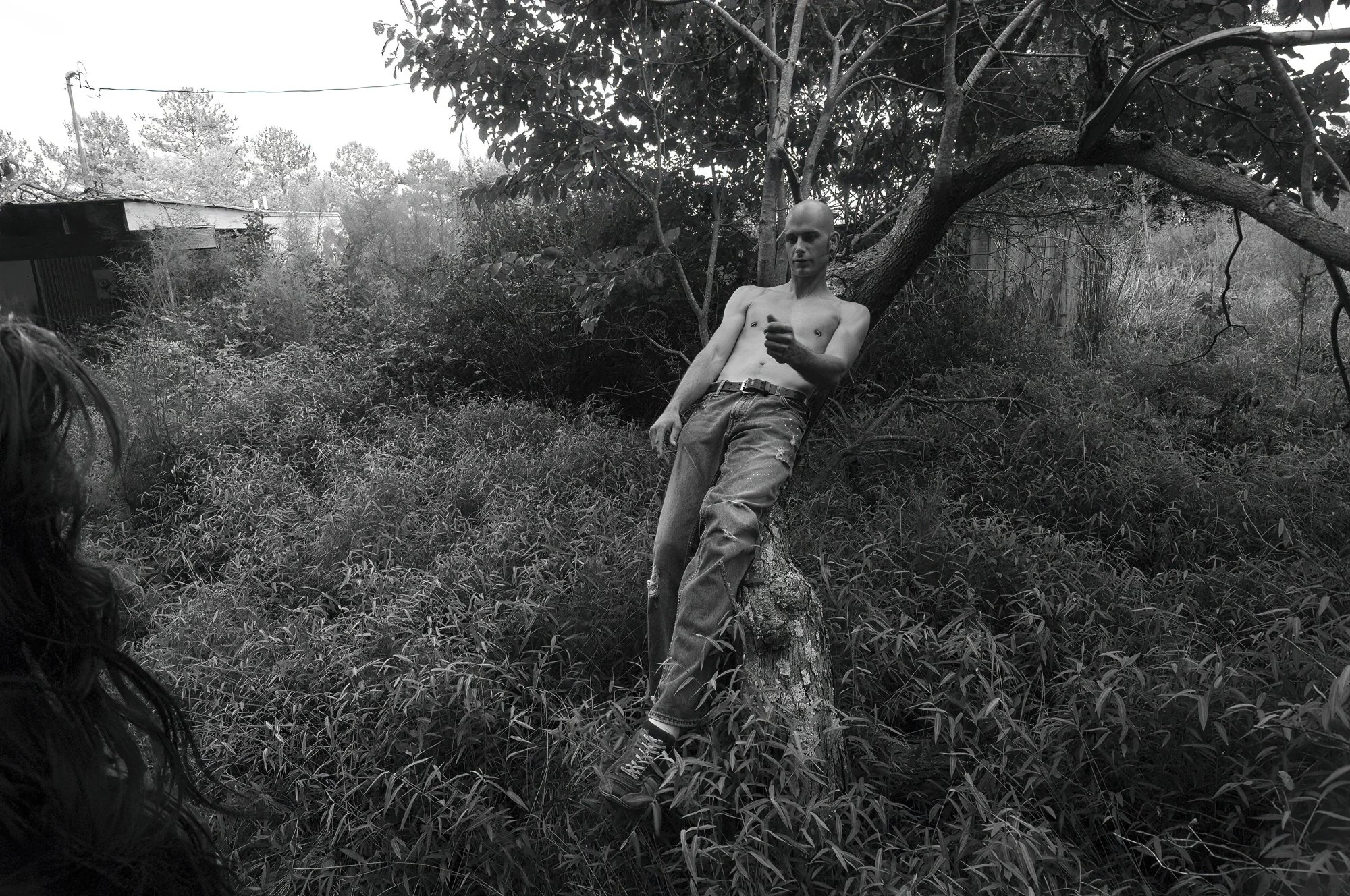

Armando. 1996

Photographer, curator, and gallery owner, John Lee Matney, gravitates towards artists who express distinct perspectives of the world. A Virginia native, Matney began his artistic career in Athens, GA when the college town was becoming a cultural hub of progressive art and music.

Predominantly black and white, scenes are variously dramatically lit, cropped, angled, and zoomed in for effect. Many works focus on the figure and include penetrating portraits, allusive nudes, and other psychologically revealing figure studies. Unexpected juxtaposition and fragmentation give some works a surreal quality. Beyond documentation, these portraits, landscapes, and figure studies reveal individuals becoming aware of themselves and their surroundings.

Matney’s use of unexpected perspectives and cropping, high contrasts, and dramatic angles capture distinct personalities and moods that range from sensuous and confident to pensive and searching.

Margaret Richardson PhD

Untitled, 1998

Still Life Detail , 1994

John Lee Matney, Jeremy Ayers, 1994, Archival pigment print

John Lee Matney, Sheila , 1998-printed 2021, Video still, archival pigment print, 24 × 35 7/10 in, Editions 1-5 of 5 + 2AP.

John Lee Matney, Ane, 1994

Psychological Landscapes

Reprinted by permission of the Athens Banner-Herald with additional material

By Melissa Link

Correspondent

Often calling to mind stills from 1920s-era cinema, Matney's photos capture the figure in various states of contortion and relaxation, creating an illusion of continued motion

Avernus, 1998

Shelia, 1998

In his current exhibit of work at X-Ray Café in downtown Athens, Virginia photographer John Matney II shows a range of figurative and multilayered still lifes offering subtle glimpses into the archetypal states of the human subconscious. Matney, who received an English degree from the University of Georgia in 1988 and then went on to study at the Art Institute of Atlanta, frequently utilizes the nude figure as a mechanism for relating inner emotions crucial to the human condition

''One of the things I struggle with when dealing with the human figure is exploring how to reconcile the dichotomy between the body and the individual in a way that doesn't seem detached,'' explains Matney of his approach to his figurative work.

''I try to integrate the immediacy of video into still photos to achieve a more diverse sense of the nude and the moment,''

Often calling to mind stills from 1920s-era cinema, Matney's photos capture the figure in various states of contortion and relaxation, creating an illusion of continued motion. Matney, whose work has received frequent awards in juried exhibits in several prestigious Washington, D.C.,-area art venues, also works in video, a proclivity that comes across in his still photographic work.

Shelia, 1998

''I try to integrate the immediacy of video into still photos to achieve a more diverse sense of the nude and the moment,'' he explains.

Occasionally using digital layering techniques, Matney adheres to traditional photographic printing processes to produce images imbued with a sense of timelessness and classicism. ''The layering creates a psychological landscape,'' he explains, mentioning his interest in the archetypal subject matter of Jungian psychology.

Such Jungian leanings are apparent in works such as ''Container and the Contained,'' a close-up facial image of an exotic dark-skinned woman leaning alongside a blank-staring human skull. The coupling of female beauty with a classic memento mori symbol offers a subtle statement on the ancient intertwining of the powers of sex and death.

The Container and the Contained, 2002, Archival pigment print, 14 × 14 in, Editions 1-15 of 15 + 2AP.

A similar sentiment comes across in several nude figurative works depicting a dark-lidded young woman in various states of struggle with an over-long strand of pearls. Calling to mind an archetypal Venus figure, the contorted movements and allusions to bondage also infer a subconscious battle involving sex, servility, anguish and ecstasy.

John Lee Matney, Pearls, 1999, Archival pigment print, 14x11 in.

Shelia, 1998

Yesterday, 2001

When I revisit this work now, I’m struck by how much of it still feels open. The photographs were made without a clear sense of destination, guided instead by curiosity, conversation, and attention. Many of the concerns that surface here interiority, restraint, the tension between stillness and movement continue to shape how I think about images and exhibitions today. In that sense, Psychological Landscapes isn’t a beginning or an ending, but a point of orientation.