Interview with Thais ShepArd — Artist & Emerging Conservator

Recorded at Matney Gallery • October 1, 2025 • Edited for clarity and flow while preserving the speaker’s voice.

Raised in Manaus and formed at Yale, Thais Shepard moves between studio practice and conservation—pressing flora into gestural prints, throwing porcelain in Kyoto, and restoring archaeological ceramics in the Amazon. Here, she talks about repair, pace, and materials that remember.

Introduction

Matney Gallery (Lee Matney): Today I’m with Thais Shepard to discuss her work, research, and plans. She recently graduated from Yale. Thais, give us a general overview—what’s been going on, and where are you headed?

Thais Shepard: I’ve kept pursuing my studies. It’s a difficult moment—nationally and globally—so defining next steps takes time, but that’s part of the journey. I’m applying to art-conservation programs, and I’m also an artist. There’s a creative side of me that loves learning how things are made and how materials work. I’m trying to combine those interests.

Studies & Early Milestones

Matney Gallery: Is there anything about your studies or your work at Yale that stood out—an anecdote, milestone, or professor who made an impact?

Shepard: For sure. In high school, art history was presented as mostly 18th to 20th-century European painting, so I thought of “art” as narrow. My first Yale art-history course, Global Decorative Arts with Professor Edward Cook, opened a whole new world—ceramics, textiles, furniture, silver, everyday objects as artistic traditions. It taught me that art is everywhere, and that objects mix and carry histories across cultures. That made me want to learn how things are made.

At Yale, ceramics wasn’t part of the art department, so I found it through residential college pottery studios—peer-run open sessions where we taught each other. After a few years I pursued a fellowship through the Yale Art Gallery to apprentice in Kyoto with a family of potters for six weeks. That was transformative.

Matney Gallery: Did you document these experiences?

Shepard:Yes, I have photos, which I’d be glad to share.

Matney Gallery: Beyond ceramics, did contemporary art, abstraction, or photography stand out?

Shepard:I took photography courses. Growing up, I shot wildlife; in New England I turned to people. One project was portraits of friends engaged with their hands—painting, playing pool. When people are absorbed in a task, they let masks fall. Those portraits felt true.

Printmaking & Abstraction

Matney Gallery: Earlier you mentioned abstraction in printmaking—what did that mean for you?

Shepard: It depends on the technique. In silkscreen, precision rules, but with monoprints I discovered freedom. Inking a plate, then using a sharp tool to move ink across the surface, I could draw gestural marks almost like painting. The process is fast and intuitive—you react to the ink’s texture, whether it’s sticky or wet, and let go of control. It helped me embrace experimentation. That gestural quality carried into my later botanical prints.

Practice & Origins

Matney Gallery: Tell me more about your art practice.

Shepard: I’m originally from Brazil—born and raised in Manaus, in the Amazon. I grew up surrounded by rainforest, so my first artworks were botanical drawings and watercolors. At Yale the world opened up: printmaking, ceramics, oil painting, embroidery, and textiles. I realized each medium has its own tempo and intelligence—pottery can be meditative; observational watercolor and oil feel almost scientific; printmaking lets me express the inner world more abstractly. I’m interested in how these modes speak to each other.

Matney Gallery: Your prints often start with plants themselves.

Shepard:Yes. I began with gestural, fast prints, then brought in literal motifs through botanicals. I press branches, flowers, and leaves—sometimes dried, sometimes fresh—so the press either leaves a colored field with the plant’s absence (a negative) or a peeled “positive” impression with fine vein detail. I arrange multiple elements so literal botany reads like gesture—reaching, falling, lingering—channeling emotions like longing.

Kyoto: Pace, Tools, and Fire

Matney Gallery: You mentioned your time in Japan.

Shepard: In Kyoto I learned traditional techniques and, more importantly, a slower pace. I’d plan simple walks on days off and let places sink in. In the studio, wooden tools designed for specific forms—bowls, cups, plates—taught precision by repetition. The glaze firing happened at an ancient kiln site using pine wood. We tended the kiln through the night. You feel how time, heat, and attention leave signatures in clay. That immersion changed how I work.

YALE: STUDIOS, COHORT, AND MUSEUMS

Matney Gallery: Any pivotal Yale experiences?

Shepard: Our senior cohort curated our thesis shows with unusual intentionality. Late studio nights built community, and many classmates are now doing residencies and exhibitions worldwide. Academically, the environment leaned toward discussion and self-direction; I sometimes wished for more explicit technique, but it nurtured creativity. The museums were essential: the Yale University Art Gallery, the Center for British Art, the Beinecke Library, and the Peabody. I interned at the British Art Center and the Beinecke, and we regularly worked in print study rooms—seeing objects up close shaped my thinking.

THESES (DEEP DIVE): METAMORPHOSIS, REPAIR, AND OPERA IN THE JUNGLE

Matney Gallery: Let’s go deeper into your three theses—the two-part studio thesis and the art-history thesis.

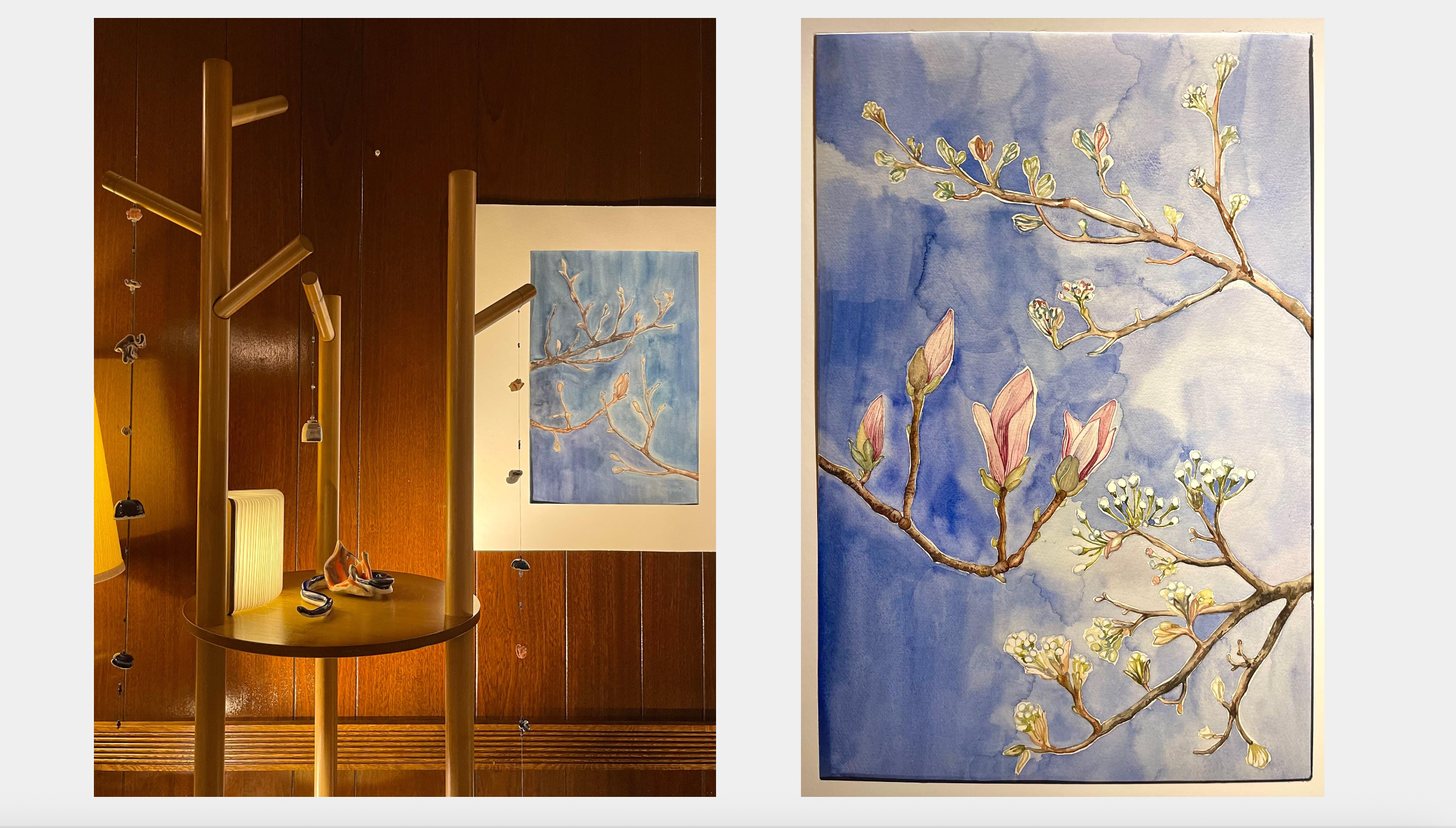

Shepard (Thesis I — Metamorphosis Pages, Watercolor + Ceramics): I was looking at Maria Sibylla Merian’s 17th-century metamorphosis plates—how multiple life stages share one page. I translated that temporal layering into watercolor sequences paired with ceramic forms. The paintings show branches moving from winter austerity toward bloom; the vessels echo stages—bud/coil, swelling, opening. Displayed together, image and object read as a single “timeline,” asking viewers to move back and forth between depiction and form. It’s about noticing change as a series of micro-events.

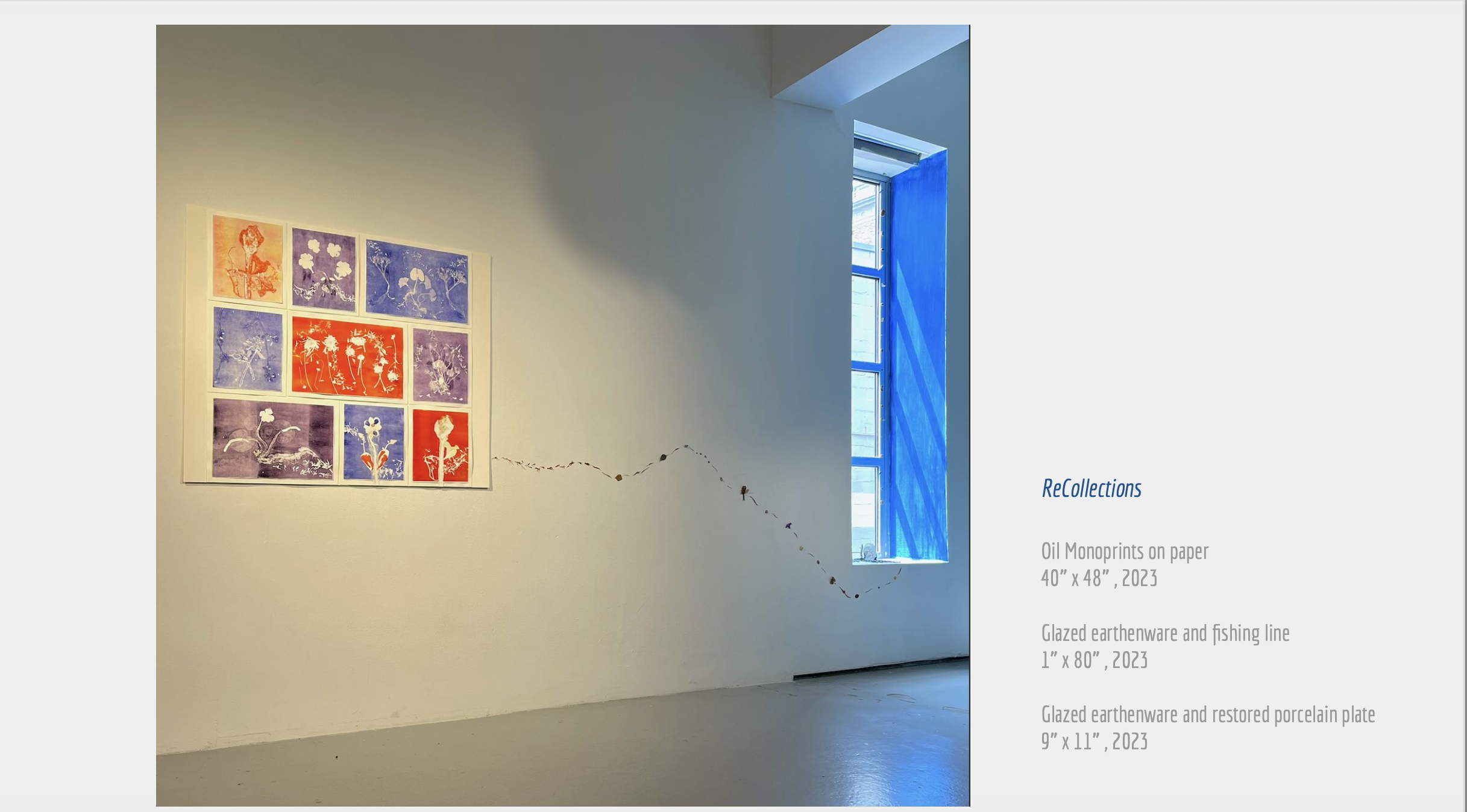

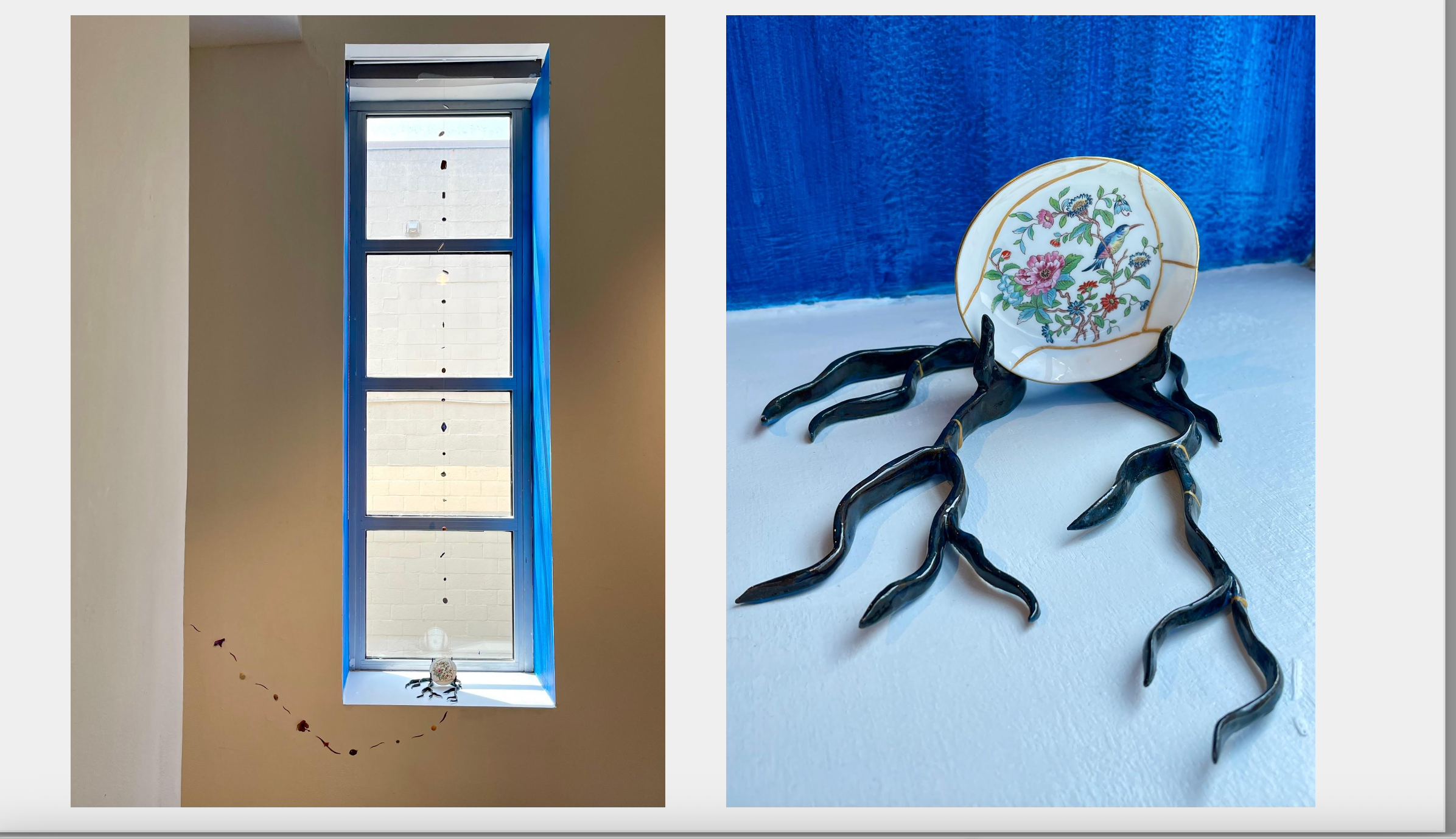

Shepard (Thesis II — Repair & Memory, Kintsugi + Botanical Prints): The second studio component centered on repair and place. I mended a porcelain plate that belonged to my grandmother using kintsugi—honoring the breakage rather than hiding it—then built a print installation that mapped my childhood bedroom. The pressed-flora monoprints function like wallpaper panels; their positive/negative impressions act as gestures—reaching, falling, hovering. Kintsugi reframes damage as history, and the “room” becomes a memory architecture where absence and presence are legible. Conceptually it dovetails with conservation ethics: when to reveal, when to conceal, how to document an object’s life.

Shepard (Thesis III — Opera in the Jungle, Art-History Analysis of Teatro Amazonas): I studied the Amazon Theater (Teatro Amazonas) in Manaus—an opera house built in the 1890s during the rubber boom and Brazil’s shift from monarchy to republic. Inside a lavish salon of Murano chandeliers and marble, I analyzed a cycle of rainforest “landscapes” and a ceiling fresco glorifying the fine arts descending into the Amazon. Reading iconography and restoration records from the 1970s, I traced political symbols (including a star associated with the republic) and staged narratives—such as stage curtains painted over monarchical emblems. The décor imports Greco-Roman ideals to assert a civilizing mission while largely erasing Indigenous presence. I also tracked how a 19th-century romanticized Indigenous novel was adapted into opera and then into painted décor—showing how literature, music, and painting re-author the same colonial story. Climate enters the critique: humidity and tropical conditions physically unsettled imported materials, so the building literally resists the narrative projected onto it.

Conservation & Restoration

Matney Gallery: You also worked with archaeological ceramics in the Amazon.

Shepard: At Museu Goeldi—one of Brazil’s major research institutions—excavated pieces arrive in fragments. I worked in the archaeological ceramics restoration lab, where we handled everything from small vessel shards to hundreds of fragments of burial urns. I learned to clean water-altered ceramics that had become porous and fragile, stabilizing them before any joins could be attempted. One project involved piecing together a plate from multiple fragments, aligning joins, filling losses with plaster, and inpainting to visually integrate the surface. In another case we processed over 200 urn fragments excavated from wet soil, carefully brushing, documenting, and cataloguing each shard. The process was slow, meticulous, and deeply humbling—an education in patience and the ethics of when to reveal and when to conceal damage.

Matney Gallery: And in New York, you engaged the field from an archival angle.

Shepard: I worked at the De Kooning Foundation in New York City, engaging with a conservation archive that ranged from treatment reports to legal documentation. The experience placed me at the intersection of studio legacy and conservation practice—seeing how an artist’s material history, from brushwork to canvas repair, is tracked and preserved. It reinforced for me the importance of documentation, since future conservators rely on these records to understand prior interventions. At the same time, being in New York was a cultural jolt: lunch breaks in Central Park, galleries and boutiques on the Upper East Side, the sense of high culture and high class all around. Coming from the Amazon, I sometimes felt out of place—“a girl from the jungle” among skyscrapers—but that contrast deepened my awareness of context, identity, and the many worlds art inhabits.

Identity, Place, and Multiplicity

Matney Gallery: How has your background shaped your eye?

Shepard: My father is an ethnobotanist and cultural anthropologist from Virginia; my mother is a French-Brazilian biologist. I’m Brazilian-American—really a mix of identities and languages. I grew up in a city of two million in the Amazon, where many friends’ families followed conventional careers and sometimes saw the forest as distant or dangerous. For me it was beautiful and worthy of respect. I think a lot about multiplicity—not belonging nowhere, but in multiple places—and how that inflects my work.

Matney Gallery: You also assisted the writer-photographer Leo Rubinfien on a Brazil chapter of his upcoming book.

Shepard: Yes. Serving as liaison and translator on a river trip pushed me to see my region anew. Being asked good questions from the “outside” made me articulate what I had taken for granted.

Fieldwork with a Writer-Photographer in the Amazon (In Depth)

Matney Gallery: You worked on a Brazil chapter with the writer-photographer Leo Rubinfien. How did that shape you?

Shepard: I served as liaison and translator while he interviewed people along the river and in Manaus. We took a boat trip, met community leaders and makers, and recorded long conversations. Being “between” worlds—local knowledge and an outside observer—made me articulate what I’d internalized. Practically, I handled consent, note-taking, and logistics; intellectually, I started to connect fine art, craft traditions, ecology, and storytelling. The project pushed me to see the Amazon not as backdrop but as a network of material cultures and lived expertise.

Matney Gallery: Did that experience loop back to your studio and conservation goals?

Shepard: Absolutely. It sharpened my ethics around representation and documentation. It also reinforced my interest in objects as carriers of place—botanical prints that register a plant’s body, ceramics that record heat and ash, and conservation records that keep an object’s history readable.

Uprooted Until Dawn Breaks, Glazed porcelain ceramics, 2024, Watercolors on paper, 2024 , 50” x 65”

Current Work & Access

Matney Gallery: What are you making now, and what do you need?

Shepard: I’m consolidating three bodies of work: gestural botanical monoprints (positive/negative suites), porcelain forms with attention to porosity and repair, and a watercolor cycle that tracks winter into bloom. I’m applying to conservation programs, and I’m seeking steady access to a ceramics studio—being away from clay has been the hardest part this year. I’m also organizing images for a website and sharing selectively on social as a way of clarifying language around the work.

Closing

Matney Gallery: Final thought?

Shepherd: Materials carry history. How we handle them—whether in the studio or the lab—is a form of care.