From the Studio and the Gallery: A Conversation with Dennis Harper.

Dennis Harper is a distinguished curator, museum leader, and studio artist whose career spans more than three decades of institutional and scholarly engagement. He has held key leadership roles at the Georgia Museum of Art and Auburn University’s Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art, where he shaped exhibitions, collections, and programs that strengthened each museum’s national profile while remaining deeply attentive to regional artistic traditions.

At the Georgia Museum of Art, Harper served as Curator of Exhibitions, organizing impactful projects including Weaving His Art on Golden Looms: Paintings and Drawings by Art Rosenbaum, the artist’s first major retrospective. Through rigorous research and scholarship, Harper positioned Rosenbaum’s work within a broader art historical framework, underscoring his own commitment to amplifying regional voices within American art.

During his tenure at Auburn, Harper advanced the museum’s curatorial and academic mission as Director of Collections and Exhibitions. He led nationally recognized exhibitions such as Art Interrupted: Advancing American Art and the Politics of Cultural Diplomacy, strengthened collections through strategic, donor-supported acquisitions, and contributed to the museum’s successful AAM accreditation. His work consistently bridged academic inquiry and public engagement, fostering interdisciplinary partnerships and expanding the museum’s role as a teaching and research resource.

In parallel with his curatorial career, Harper has maintained an active studio practice centered on egg tempera painting. His deep material knowledge and grounding in traditional techniques inform his curatorial perspective, lending nuance to his interpretation of painting across historical periods. This dual role—as maker and scholar—has shaped a thoughtful, integrated approach to exhibition development, collections stewardship, and museum leadership, and continues to inform his contributions to the field through mentorship, professional service, and public scholarship. In the conversation that follows, Harper reflects in his own words on these experiences, considering how curatorial practice, institutional responsibility, and studio work have informed one another over time.

Museum Experience & Curatorial Vision

You’ve held curatorial leadership roles at the Georgia Museum of Art and the Jule Collins Smith Museum. How did those institutional contexts shape your approach to exhibition-making?

Before I arrived at either of those museums, I had worked for several years in exhibition preparation and design—the practical side of getting an exhibition installed in a gallery and shaping its presentation to steer a viewer toward a specific encounter with the art. So, when I began to work as a curator, I couldn’t help but consider the visual or physical aspects of an exhibition’s composition alongside its conceptual or educational intent. I believe they can and should support and inform each other. Sadly, I’ve visited exhibitions which felt more like flipping through pages in a book instead of engaging me in a broader way. I always tried to craft an exhibition experience that wasn’t so rote or mechanical. The great thing about both museums you mention is that they are academic institutions, which required pitching exhibition content to a deeply inquisitive, well educated, and demanding audience. That’s not to say that we didn’t also make exhibitions accessible to general or casual visitors, but we had to up our game, so to speak. The intellectual thesis for an exhibition, research and texts, installation craft, and related programming all were expected to be of a high order. In short, they taught me to do better work.

Many of the exhibitions you curated—such as Art Interrupted and the Art Rosenbaum retrospective—blended scholarly depth with regional focus. How do you balance academic rigor with accessibility in your curatorial work?

Weaving his Art on Golden Looms: Paintings and Drawings by Art Rosenbaum exhibition installation views, Oct 2006–Jan 2007, Georgia Museum of Art

Weaving his Art on Golden Looms: Paintings and Drawings by Art Rosenbaum exhibition installation views, Oct 2006–Jan 2007, Georgia Museum of Art

I try to see each project the way different audiences might view it, and ask myself: What will they get from it, what could challenge them, or interest them? I’ll admit, it can be difficult to include specialized information that may be engaging to some without turning off other viewers who don’t understand or even want that type of content. And vice versa. In wall text or catalogue copy I try to write about complex or specialized subjects in a plainly worded, straightforward manner—although I know I don’t always succeed. My intention is to provide a kind of ladder, from simple descriptions to more involved ideas, and people can opt out at whatever rung they find boring or frustrating!

What exhibitions are you most proud of from your time in the museum field, and why? Were there projects that felt especially personal or transformative?

Several come to mind, but I’ll limit my answer to a couple. One was a small survey of video and computer-based art that I organized for the museum at Auburn University (Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art). It included artists from across the US and abroad working in a variety of media from “traditional” video shot through a camera, to computer-assisted animation derived from the artist’s woodcuts, “un-winnable” gaming formats, and many other approaches to making art that exists only on digital screens. It was the first such exhibition at that museum and, honestly, I wasn’t sure how the community would respond. I was pleased by its positive reception. I remember looking in the galleries one morning shortly after the museum doors opened to find an elderly gentleman reading the intro panel. An hour later he was still in the space and standing transfixed amid a multiple-monitor environment. Later still, I found him seated at a kiosk with joystick in hand working at an interactive piece. One of my takeaways from the exhibition was never to underestimate your audience.

The last exhibition I mounted at Georgia Museum of Art was particularly meaningful to me. It showcased the artist’s books of David Sandlin. Born in Belfast, Northern Ireland, David is a longtime friend of mine dating back to undergraduate school. I love his paintings, prints, drawings, and books; but while employed at public institutions I felt it would be a professional conflict of interest to exhibit artists whose work I collected or who were close friends. Fortuitously, since he was serving that year as the Lamar Dodd Artist in Residence at UGA and thus due an exhibition, my ethical dilemma got tossed. In fact, it would have been a grievous disservice not to show his work! If you don’t know David’s art, you should look him up. He’s wildly inventive, technically amazing, highly literate, and downright funny. Although he’s lived in New York for the past forty-some-odd years, it’s his childhood experiences in Belfast during the “Troubles” and an uprooted life in rural and suburban Alabama that figure most prominently in his art.

In projects like From Her Innermost Self, you helped bring attention to visionary women artists of the South. How important is cultural advocacy in your curatorial philosophy?

Honestly, I considered it a great privilege to be a curator at a public institution. And I truly believed that the word “public” meant that my responsibility was to represent and engage all individuals and groups that make up a community. I tried to be inclusive in acquiring a wide range of art forms from diverse makers for the museum’s collection. The same was true for the exhibitions I developed. In part (and perhaps selfishly) it was simply fun to explore the variety of art-making that exists outside the familiar names and categories that are most often presented. There is so much art out there, and good art, which often goes unnoticed for any number of reasons. “Less well known” does not mean “less important.” Those artists deserve to be seen and discussed. It also enriches the lives of art-viewers to experience art that is unfamiliar to them.

As someone who’s also an artist, how has that shaped your understanding of the artist-museum relationship? Do you think it gives you a different sensitivity as a curator?

Well, yes, I do believe that someone who is seriously engaged as an art maker might have a slightly different attitude or expression in curatorial work than those who aren’t. That is not to say that artists make better curators or better museum workers in general. In fact, I often had a feeling of “imposter syndrome” since my educational background was not art history or museum studies. What I do believe is that artists who also curate bring to the role a level of familiarity with art materials, processes, and even the creative compulsion, that others might not possess. And that can affect their curatorial output. An artist may provide insight into a work of art that goes beyond a description of its finished state or historical context. As for the intricacies of the artist-museum relationship, all I can say is that having worked in both studio and gallery circumstances, I am sympathetic to the difficulties and expectations of each side.

B&W Dream, 2001, egg tempera on panel, 9 x 11 1/2 in., coll. Georgia Museum of Art

Artistic Practice & Egg Tempera Portraiture

How did your experience working in major museums influence your decision to focus on portraying artists—especially those working in Georgia and the South? Your portraits often depict fellow artists in their studios. Do you see this series as a curatorial act as much as a painterly one?

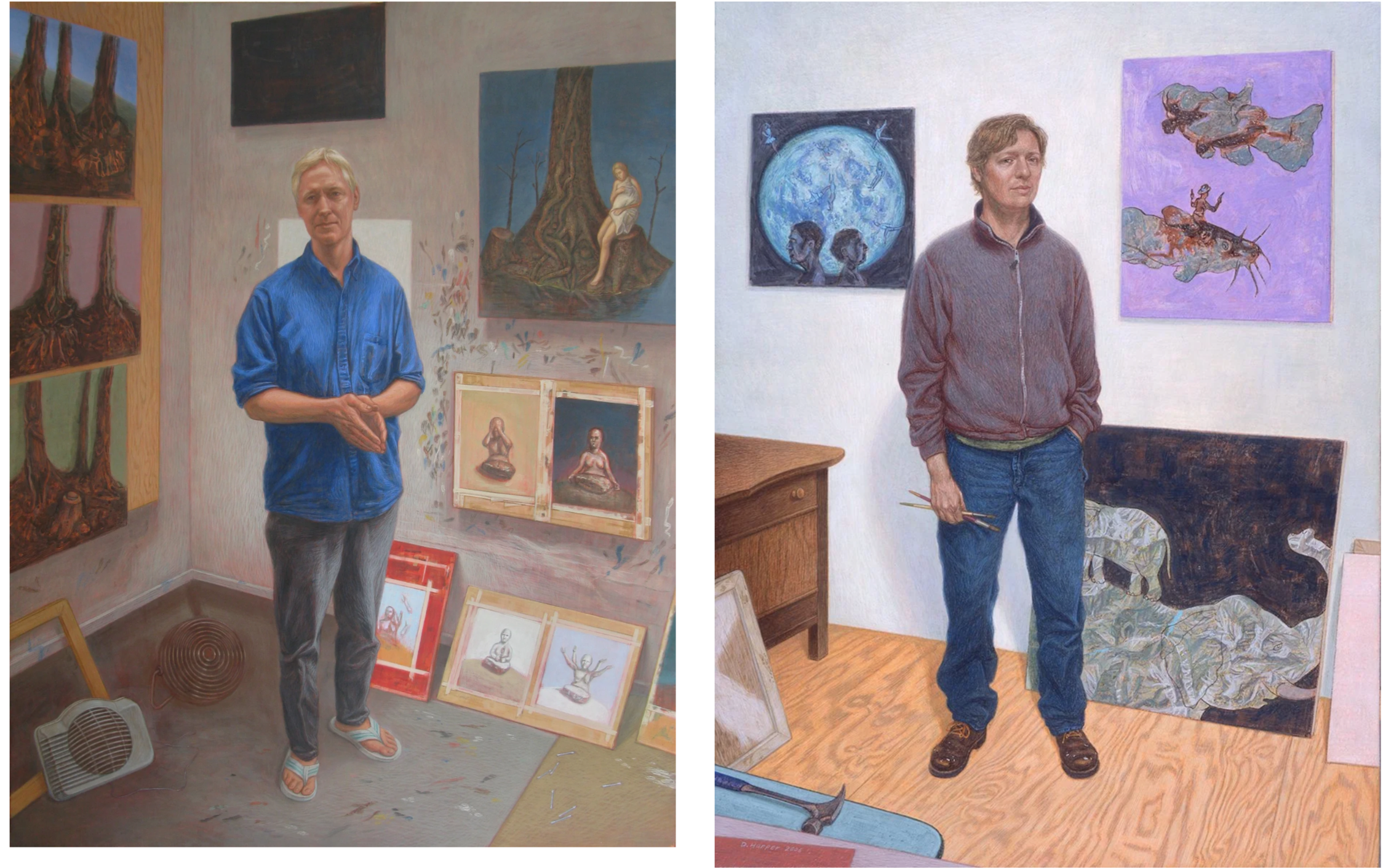

Scott Belville in his Studio, 2009, egg tempera over casein on panel, 28 x 22 in. (left), Jeffrey Whittle in his Studio, 2006, egg tempera over casein on panel, 21 x 16 in., private collection (right)

I’ll try to answer these two questions together. As a younger artist, my inspiration and influences often came from artists of the past whose work I admired. I hope I wasn’t being too imitative, but I found that I could better appreciate their work by emulating it in some way. That curiosity is probably what led me to a museum profession. I loved looking at art, and later handling it, about as much as I loved making it. Of course, both as an artist and as a museum curator, I came to know and develop friendships with many living artists. Besides admiring their work, I felt great respect for their perseverance and ability to make a life as an artist. The artists that I have depicted in my portrait series are all friends of mine who have achieved varying degrees of “success” in their field. What unites them most is their dedication to their practice. I wanted to portray them in their studios surrounded by works in progress. Naturally, I tried to achieve good facial and gestural likenesses. But I felt, too, that their art and working spaces were equally reflective of their individual natures, so I tried to capture that milieu as a kind of material portraiture as well.

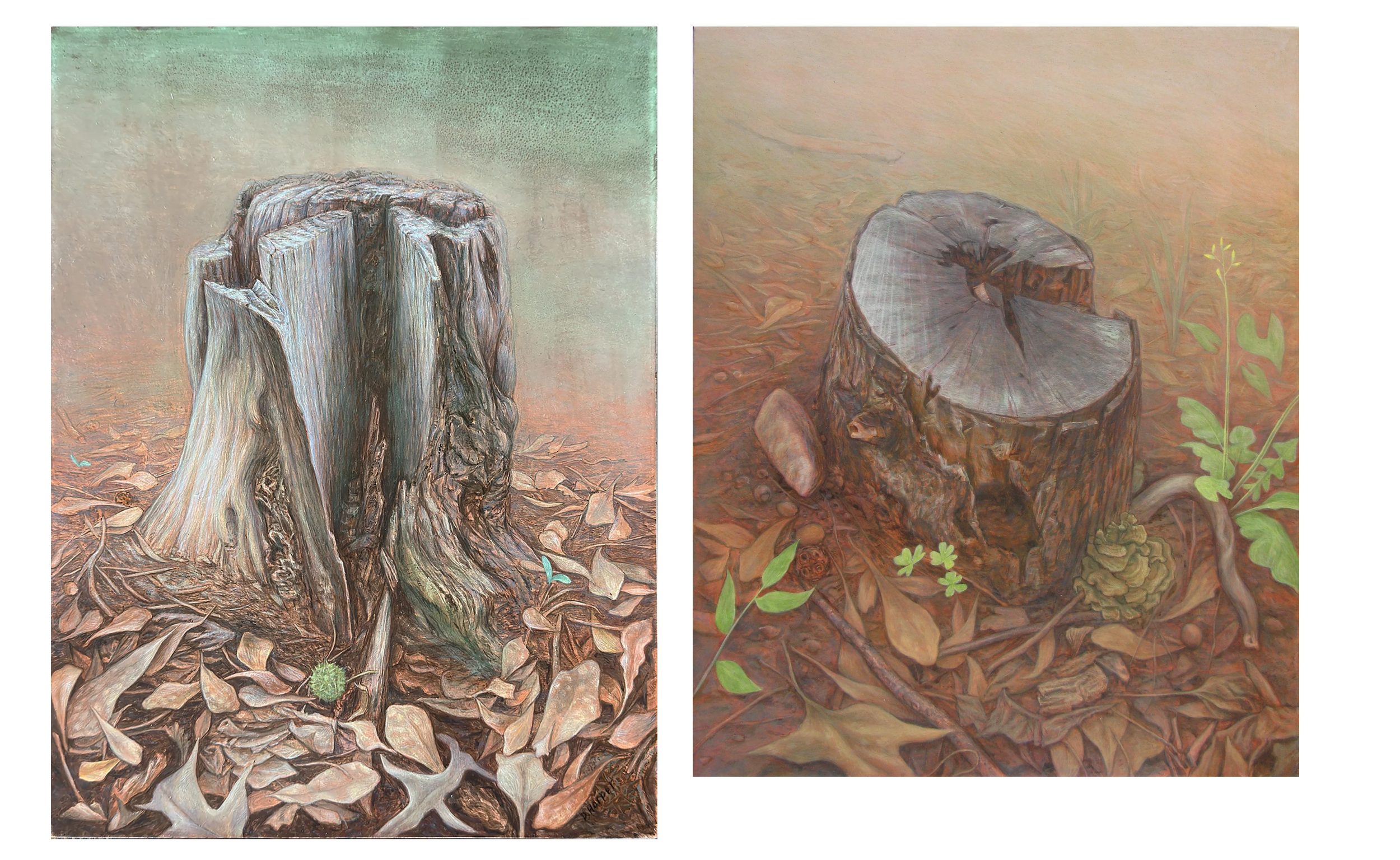

I don’t really think of my artists’ portraits as a curatorial act, no more so than any artist basically “curates” their subject matter. Artists make choices about what they want to paint or sculpt or photograph, or whatever media they use, and investigate that subject through unfolding iterations. These portraits aren’t intended as documentation, either, except maybe as a personal record, not unlike the remembrance of a friend in a diary. You didn’t bring up my paintings of stumps and broken trees as a subject for this interview. You might be interested to know that I regard them as portraits, too. In those paintings I focus closely on what I think of as heroic living forms, victims of harsh adversity or neglect, where a narrative of their lives is spelled out in twisting shapes and jagged cuts. I try to paint them with the sort of dignity evidenced in the best of human portraiture. As with my artists’ portraits they are a kind of homage to tender my respect.

Art Rosenbaum in his Studio, 2005, egg tempera on panel, 15 x 15 in., private collection

Tempera painting is unusually slow and detailed. Do you find that this method gives you more time to contemplate your subject—and does that mirror your curatorial process in any way?

The way I work with egg tempera is indeed a slow and methodical process. It doesn’t necessarily have to be that way and in fact many 20th-century and contemporary artists have taken a faster, more spontaneous approach to the medium. Ben Shahn, for one. However, I use it in a manner that is more akin to the way early Renaissance painters worked. I won’t go into the technical procedures involved, but in general the process I follow segregates the many decisions and activities that are juggled to create a painting into a sequence of isolated, individual, and incremental steps. Instead of trying to manage dozens of decisions simultaneously, I can direct my attention to a single task, then move on to the next step. It may sound stifling or formulaic, but to me it’s not. This deliberate pace, in a way, slows down time. As you said, it provides more time to contemplate my subject. I can let my imagination wander as I carry out a relatively routine task on the painting surface. The painting evolves gradually, in phases, but not to a predestined outcome. I can still make fundamental decisions and changes along the way. From a practical or logistical viewpoint, I found this method also accommodated my curatorial “day job” well. Since I didn’t have long stretches of consecutive hours to work in my studio, this manner of building a painting—and the use of egg tempera itself—afforded the possibility to stop and restart working without a negative effect, which is something I couldn’t accomplish as easily in oil painting.

To address the second part of your question, I suppose this does mirror my way of working as a curator. My writing is certainly slow and laborious, with constant deliberations and incremental changes. An exhibition’s thematic underpinning and checklist of objects similarly evolve from a skeletal structure to fleshed-out form. Each task may be conducted separately, but they grow out of the previous one and support the next to produce (with luck) a compelling exhibition. I wouldn’t say that my work as an artist steers the way I work as a curator, or vice versa. Instead, I suppose the similar approaches in both pursuits are just different manifestations of my personality quirks. I probably work through other undertakings the same way. It’s the way I’ve developed to help me navigate through life.

Connections Between Roles

Now that you’ve stepped back from day-to-day museum work, how do you envision the next chapter of your creative and scholarly life? Do the two still feed each other?

Outskirts Onagers, 2001, egg tempera and gold leaf on panel, 18 1/2 x 11 1/2 in.

I found great satisfaction over several decades musing on art, doing research and writing about it, presenting exhibitions that attempted to elucidate some aspects of it, and sharing the pleasure it gives me with others. A nice bonus was that I got paid to do so! But now that I am settling into retirement from museum work, I look forward to having more time to devote to my first and always-primary interaction with art: the making of it. I have written a few short texts for publication since leaving Auburn, though I admit I now find it more difficult to translate my rambling thoughts into cogent paragraphs. As I am now preparing to set up a studio in a new town and new home, I’m eager to unpack my brushes and jars of pigments and get back to work.

Sticks and Stones 4, 2012, Egg tempera over casein on panel, 18 x 24 inches

Landscape with Stump, 2012, Egg tempera over casein on panel, 9 x 9 inches

Sticks and Stones 3, 2012, Egg tempera over casein on panel, (Varnished and waxed) 12 x 9 inches (left), Sticks and Stones 1, 2012, Egg tempera over casein on panel, 14 5/8 x 11 ¾ inches (right)