Neil Duman: Letting Glass Be Glass

A Conversation

Neil Duman has spent decades working at the intersection of control and surrender, allowing glass to assert its own intelligence within the sculptural process. In this conversation, Duman reflects on his formative years at VCU, his early embrace of experimentation, and the moments that shaped his lifelong commitment to material-led making. Moving between studio practice, teaching, collaboration, and public work, he speaks candidly about risk, intuition, and the discipline required to “let glass be glass.” What emerges is a conversation grounded in material knowledge, attention, and a commitment to work that rewards long looking.

Neil Duman:

My journey really began when I transferred to VCU. I had been at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore, where my main emphasis beyond foundation was metalwork and jewelry design. When I transferred to VCU, the school assigned Kent Ipsen as my advisor, and he suggested glass. He had just started the glass program the year before and needed one more student in his studio class. He suggested glassblowing, which I had never really heard of or thought of as an art medium.

The class met at eight o’clock on Monday mornings. The glass studio was behind the president’s office in this old lean-to building that Kent had actually built himself. When I walked in, it was dark, no natural light at all, just the glow of the furnaces and glory holes, and a few incandescent bulbs. But the sound, the heat, the feel of the room, it was incredible.

When I watched that first demonstration, seeing the glass come out as a liquid and then suddenly turn solid as it passed through that critical point, capturing movement as it froze, it completely hooked me. In all of my earlier work, whether in wood or metal, movement had always been important to me. Glass felt like a natural extension of that. I was immediately drawn to it, and I have been working with glass ever since. Meeting Kent and coming to VCU completely changed my trajectory as an artist.

Originally, I thought I was going to be an art therapist. At that time, you did your undergraduate degree in art and then went to graduate school for the therapy part. I imagined myself doing therapy work and maybe jewelry on the side in a small private studio. But after that first glass class, all of that disappeared. I knew I wanted to work with this material.

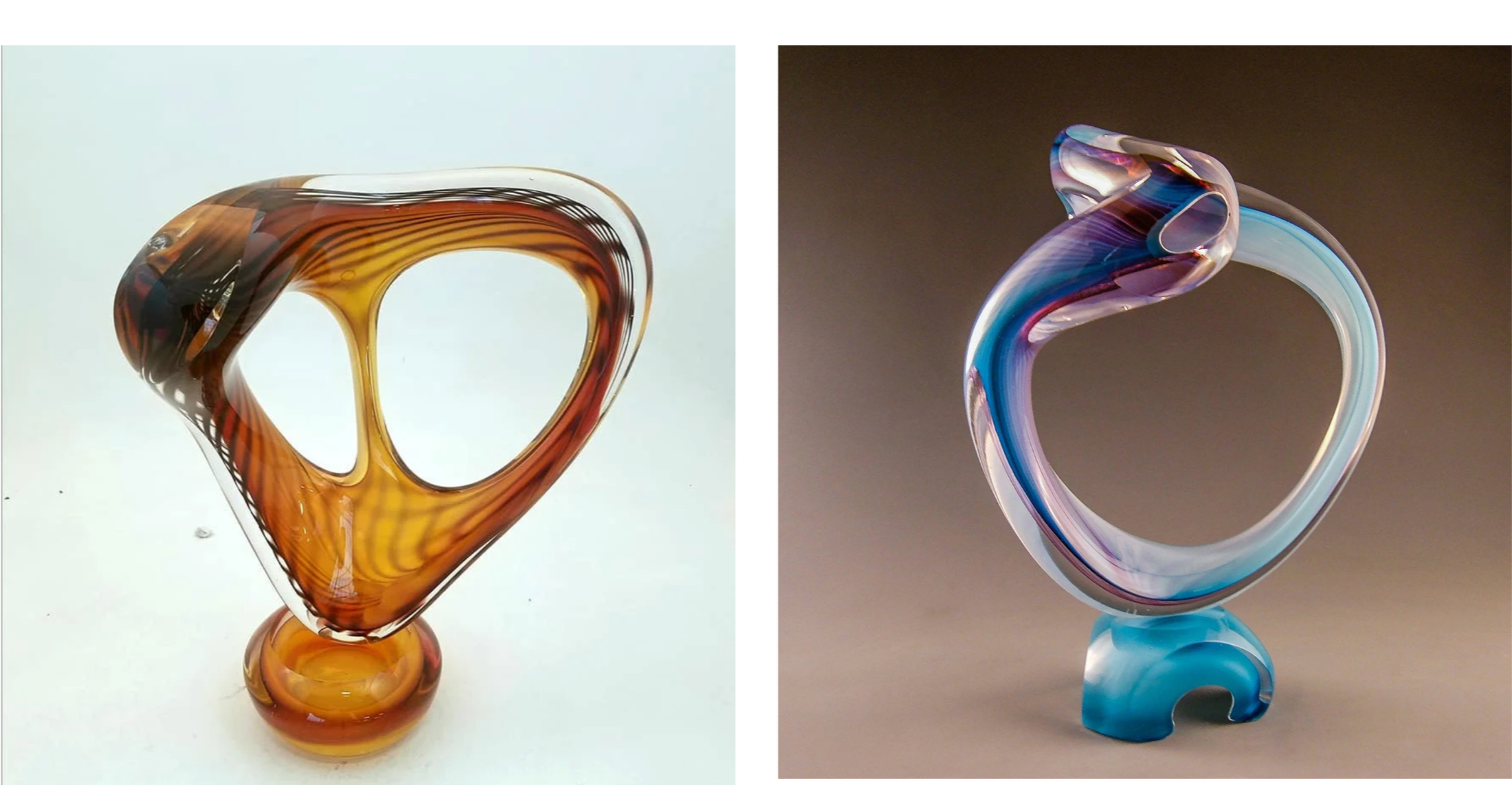

Held Vase Series

(left) This series explores structural interdependence through the pairing of two distinct glass forms. Each element relies on the other for balance, creating a unified object through contrast and mutual support.

Untitled

(center) A return to an early formal idea first explored decades ago, revisited with a fully developed technical vocabulary. This work marks the beginning of an ongoing investigation the artist intends to expand.

Balanced Sunset

(right) Part of the Balanced Life series, this work reflects the artist’s sustained interest in equilibrium. Stacked elements evoke both the visual harmony of sunset color and a personal meditation on balance

Lee Matney:

What were your earliest sculptures like?

Neil Duman:

From the beginning, my work involved a lot of manipulation of the material. I had worked with clay, and you can push and shape clay directly with your hands. Glass does not allow that. You need tools. But the impulse was the same. I was always drawn to Henry Moore’s sculpture, especially the way he used open space, the voids within the form. That idea of space being as important as mass found its way into my work very early on.

Movement was always there. Even before I started piercing forms or creating openings, the sense of motion was essential.

Before VCU, in high school, I was selected to attend I.C. Norcom, the first experimental high school in Virginia. Different schools in Portsmouth nominated students, and I was selected for the art program. That is where I started welding and working with metal, and I loved it. That experience definitely fed into everything that came later.

After finishing my undergraduate degree at VCU, I was working with experimental materials, glass and metal, and I decided to stay on for graduate school mainly to continue working with Kent. His philosophy was that glass was an experimental material. He was not interested in rules or tradition. His attitude was, do not worry about what has been done, just find out what can be done. Everything was open. If I wanted to pour ten pounds of molten glass into a hollow tree trunk just to see what happened, that was encouraged.

So I stayed. I was also a graduate teaching assistant, and honestly, I did not enjoy that part. Teaching took time away from my own work, and I struggled with that balance. At the time, I was not interested in teaching. Later, I discovered that I love teaching and that I am good at it. I now teach workshops and classes at community art centers and in my own studio.

A Workshop at the Studio

Documentation from a small, family-centered glass workshop. The artist emphasizes accessibility and process, beginning with a demonstration before inviting participants into hands-on making.

Then Harvey Littleton came to critique our work. Harvey, along with Dominick Labino, was one of the founders of the contemporary studio glass movement in the United States, and Kent had been one of his first students. During the critique, Harvey asked me why I was in graduate school. I told him I wanted to learn. He said, “You will learn more setting up your own studio in your backyard than you ever will in school.”

That conversation changed everything. I dropped out of grad school, built a studio in my backyard, and started developing a voice that was truly my own. I was working alone, just me, my thoughts, my ideas, and the material. When I felt I had something worth showing, I stayed in close contact with Kent. I would call him and say, “I am working on this idea. Can I come show it to you?” He would critique the work, and I would go back and keep pushing.

At that time, I was not interested in teaching. Later, I discovered that I love teaching and that I am good at it. I now teach workshops and classes.

Lee Matney:

Your work is very recognizable, but you also seem resistant to being boxed into one style.

Neil Duman:

That’s always been a challenge. I love experimenting and working across a wide range of techniques, and that doesn’t always align with how galleries like to operate. They often want a clearly defined, instantly recognizable style. I do have styles that people recognize as mine, especially the free flowing sculptural forms with openings, where the color is usually inside the piece rather than on the surface.

Autumn

(left) This work draws its palette from the late-autumn landscape, informed by seasonal hikes and close observation of color shifts in nature. The composition reflects an attentiveness to atmosphere, memory, and place.

Storm over the Gulf

(right) Inspired by exhibitions along Florida’s Gulf Coast, this piece translates environmental experience into color. Deep blues reference the water, while layered purples echo distant storm formations on the horizon.

I like to play with how clear glass refracts and reflects light, how it picks up its surroundings and incorporates them into the piece. If the color is only on the exterior, the form can feel isolated. Clear glass allows the environment to become part of the work. It also magnifies interior elements and interacts with light in more complex ways.

I’ve never done a show that focused on only one technique or one narrowly defined style. Most exhibitions present a group of works or a progression over time. Some forms I’ve been working with for more than forty years, and I still love them. At the same time, I always set aside time to try something new.

Lee Matney:

Can you talk about River Grass, the piece currently at the Muscarelle?

Neil Duman:

That piece was included in the Liquid Commonwealth exhibition at the Muscarelle, and I was very fortunate to be part of that show. The work is called River Grass IV. It’s the fourth piece in that series.

When I lived in Richmond, I worked for a whitewater rafting company. In the summer, it was much more enjoyable to get paid to go down the river than to be stuck in a hundred degree glass studio. As we floated down the river, I became fascinated by the grasses growing up from the riverbed. They’re submerged, but still vividly green, moving back and forth with the current. You can see different currents depending on the depth of the water, and the grasses respond differently to each one.

River Grass 4.0

Inspired by quiet observation of river currents, this piece captures the rhythmic movement of grass responding to layered flows of water and light. The work emphasizes repetition, stillness, and temporal change.

I found it incredibly meditative, just sitting on the raft, looking down, watching that movement. I wanted to capture that feeling in glass. River Grass IV comes directly from those moments on the river, which were some of the most peaceful times in my life. On the river, you’re moving gently, while everything beneath you is in motion. In the studio, it’s the opposite. You never stop moving.

I’ve done other river inspired pieces too, including works where glass wraps around stones. I would coat a rock, pour molten glass around it, anneal the piece, then remove and clean the rock and reassemble it. I haven’t done one of those in a while, but there are many ideas I’ve explored once or twice and hope to return to. Time is always the limiting factor.

Lee Matney:

Your relationship with control seems central to your practice.

Neil Duman:

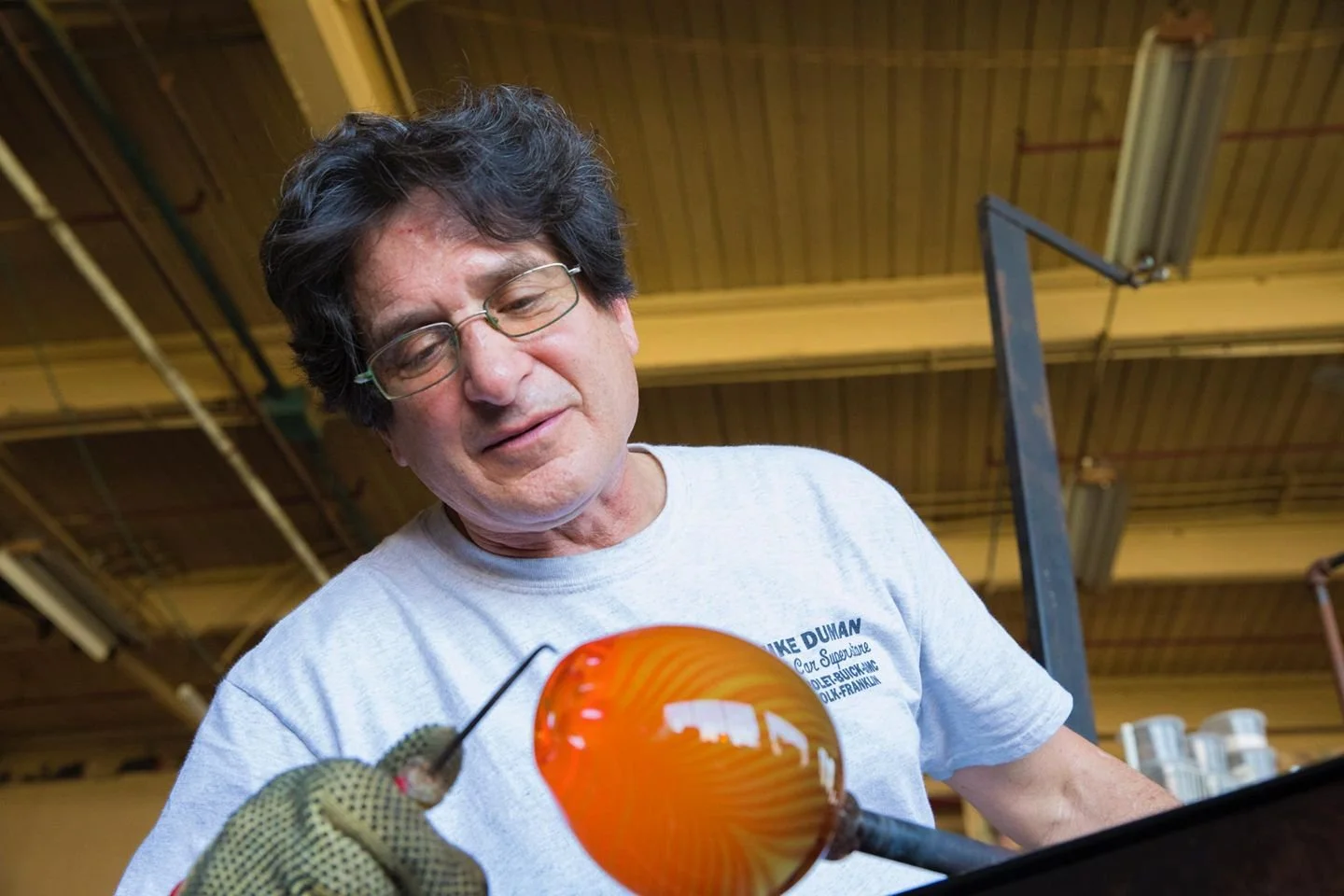

Very much so. One of the most important lessons Kent taught me was to let glass be glass. You never want complete control. Maybe seventy percent control, but glass has to have a voice. It has to participate.

Reflected Sunset

(left) This piece interprets the optical phenomenon of sunset light reflected across a body of water, translating reflection into layered color and surface interaction.

Blue Wave

(right) A minimalist work focused on clarity, precision, and formal restraint. Color and movement are distilled into a clean, rhythmic gesture.

When I go into the studio, I might have an idea about size or number of openings, but I let the material guide the final form. My color choices often come from nature, sunrises, sunsets, light through leaves, stones in mud. I used to do a lot of photography, especially close ups, and that still informs how I see color.

As I’ve gotten older and more technically skilled, it’s actually become harder to let go. Commission work makes that especially challenging. If a client wants a piece to be eighteen inches tall and the glass clearly wants to stop at sixteen, forcing it almost always makes the piece worse. I’ve learned, sometimes the hard way, that the best work happens when I listen and let the glass finish itself.

Lee Matney:

You’ve also collaborated with other artists.

Neil Duman:

I love collaborating. I’ve worked with metalworkers, woodworkers, potters. Buck Dally, a metalworker on the Eastern Shore, and I did a number of collaborations, including a show called Fire and Ice at the former Cristallo Gallery in Williamsburg. We had a lot in common, both working out of backyard studios, building our own equipment. That shared mindset made the collaborations very natural.

I’m always open to collaborating when there’s a shared sensibility. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. That’s part of it.

Lee Matney:

What about public work?

Veiled Plate (Detail)

(left) A downward view emphasizing surface and translucency, revealing the subtle layering and veiling effects achieved through the glass.

Detail: Layered Color Structure

(right) Close view highlighting the interaction of multiple colored layers. The image emphasizes depth, transparency, and the cumulative effect of sequential glass applications

New Psalmist Baptist Church (Site-Specific Installation)

Designed for New Psalmist Baptist Church, this work incorporates birds symbolizing the Holy Trinity. The supporting metalwork was fabricated in collaboration with Buck Doughty and engineered to integrate with the window architecture, framing the cross visible through the glass.

Neil Duman:

The public piece I’m most proud of was for New Psalmist Baptist Church in Woodlawn, Maryland. They were building a new sanctuary, and I was asked to create a glass work referencing the Holy Trinity. We settled on birds, three birds in flight. One with wings down, one mid stroke, and one with wings fully extended above the others.

Each bird had a forty two inch wingspan, balanced on a very small base. Buck Doughty helped fabricate the metal armature. When the piece was installed, it was positioned so that as people exited the sanctuary, they encountered these three birds suspended in space. It was incredibly powerful.

Most of my other public works are in corporate settings, bank lobbies, boardrooms. There’s a piece at the Federal Reserve Bank in Richmond that responds to the James River, visible through floor to ceiling windows. Those kinds of commissions really resonate with me.

Site-Specific Wall Works (Pair)

Two wall-mounted glass works created in direct response to architectural context, emphasizing scale, placement, and spatial dialogue.

Lee Matney:

Your work feels very tactile and inviting.

Neil Duman:

I’m fine with people touching my work. There was even a show once designed specifically for tactile experience, where visitors were blindfolded and explored the pieces through touch. My forms have subtle curves and indentations, and I think they make people feel good. They put me in a good place when I make them, and I hope that translates to the viewer.

Glass is naturally fluid. If I tried to achieve the same softness and motion in metal or wood, it would take an incredible amount of time. Glass wants to move. I have ADHD. I don’t like sitting still. Glass doesn’t either. We work well together.

Lee Matney:

Do you see changes ahead in your work?

Neil Duman:

I’ve always changed. I don’t plan change in a deliberate way. I respond to ideas when they arrive. There are still plenty of things I haven’t done. Stained glass probably isn’t one of them. I don’t have the patience, but collaboration could open that door in a different way.

Glass is immediate. You can have an idea, make a prototype, and know within a day whether it works. That’s one of the reasons I love it. It’s forgiving. You can change direction mid process. That’s much harder in metal.

I can’t imagine not working with glass. From the first moment I walked into that studio at VCU, the sound, the glow, the movement, I’ve never stopped being enthralled. One of the hardest lessons I’ve learned is being willing to destroy a good piece in order to make a great one. If you’re not willing to risk that, you’ll never make your best work.

Cut Paperweight Study

(left) A playful yet technical exploration of internal color layering. The paperweight was intentionally cut open to reveal its complex interior structure.

Layered Color Experiment

(right) An experimental work investigating multiple methods of color application across distinct glass layers, emphasizing process, variation, and material curiosity.

Neil Duman in the studio

Balanced Sunset

Part of the Balanced Life series, this work reflects the artist’s sustained interest in equilibrium. Stacked elements evoke both the visual harmony of sunset color and a personal meditation on balance.