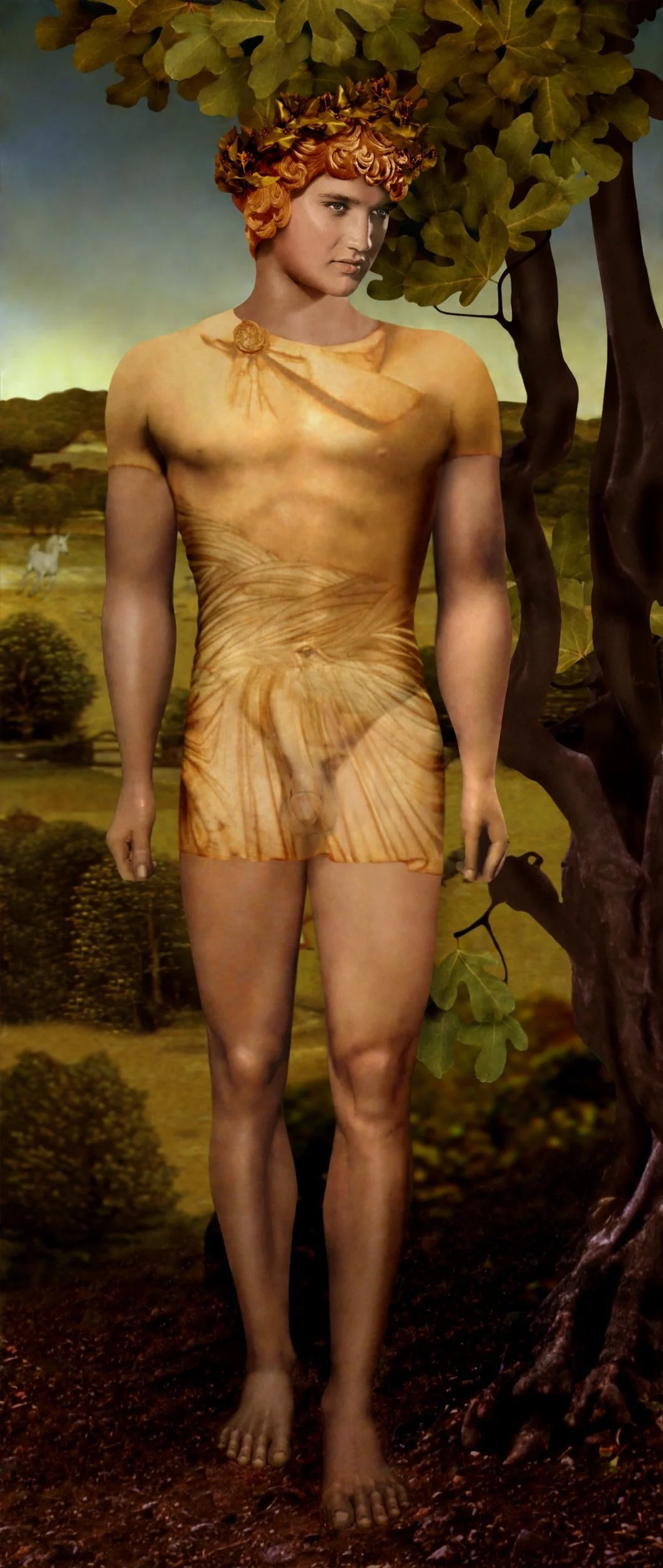

Olga Tobreluts

Adam

2006 (printed 2010)

Kodak Metallic print

Edition 1 of 5

71 × 28 inches

Refiguring the Classical Body: Ivan Plusch and Olga Tobreluts in the Aftermath of Empire

The classical body has long functioned as one of Western art’s most persistent structures. From antiquity through the Renaissance and into the academies of the nineteenth century, the human figure served as an index of proportion, beauty, and moral order. It anchored architecture, stabilized civic space, and projected narratives of permanence. Even in moments of political upheaval, the classical form often re emerged as reassurance, a visible promise of continuity. Yet the classical body has never been innocent. It has been mobilized to signal authority, cultural supremacy, and ideological coherence. It has been pressed into service by empires and nation states, sanctified by academies, monumentalized in stone. To return to it in the twenty first century is not to revisit a neutral aesthetic language but to enter a charged terrain of inheritance.

The work of Ivan Plusch and Olga Tobreluts engages precisely this terrain. Emerging from post Soviet cultural conditions in which the classical canon carried both historical weight and ideological residue, each artist approaches the body not as decorative motif but as structural inquiry. Their practices unfold along different material and conceptual lines, Tobreluts through digital reconstruction and painterly myth, Plusch through dissolution, entropy, and temporal instability, yet together they articulate a rigorous reconsideration of figuration after empire.

Olga Tobreluts

Antinous

2019

Stereo-Vario

Master edition 1 of 3, copy 10

40-inch diameter

Olga Tobreluts

Antinous

2012

Kodak Metallic print

Edition 1 of 5

22 × 21 inches

Olga Tobreluts came of age in Leningrad during a period of profound cultural transition. In the early 1990s, as the Soviet system collapsed and new artistic vocabularies began to surface, she became associated with the Neo-Academism movement in St. Petersburg. Neo-Academism did not simply revive classical aesthetics; it examined them. The movement reengaged Greco-Roman and Renaissance forms at a moment when ideological certainties were unraveling. In this context, classicism functioned less as nostalgia than as critical instrument. Tobreluts’ early digital works are central to this history. In her Models series of the mid 1990s, she employed emerging 3D modeling software to reconstruct idealized figures drawn from classical prototypes. These bodies, poised and anatomically refined, appeared at once ancient and contemporary. Rendered through the sheen of digital surfaces and often contextualized within fashion inflected or media saturated environments, they unsettled the assumption that antiquity belonged solely to marble and museum vitrines.

The significance of these works lies not merely in their early adoption of digital tools but in their conceptual precision. Tobreluts reframed the classical body as image, reproducible, modifiable, mediated. In doing so, she exposed the constructed nature of the ideal itself. The ancient figure, so often treated as stable and timeless, became contingent upon software, code, and technological systems. Antiquity was not revived; it was reformatted.

Olga Tobreluts

Cain and Abel

2012

Kodak Metallic prints

Edition 1 of 5

32 × 40 in.

This move carried particular resonance within a post-Soviet environment where official aesthetics had long been entangled with ideological production. Socialist Realism had instrumentalized the body as emblem of strength and moral clarity. Monumental statuary had projected narratives of collective endurance. Against that backdrop, Tobreluts’ digitally reconstructed bodies functioned as both citation and critique. They retained beauty and proportion, yet their mediation through contemporary technology made visible the artifice underlying any claim to timelessness.

As her practice evolved into large scale oil painting, the classical impulse did not disappear. Instead, it migrated. Works from the 2000s and 2010s continue to draw upon mythological and Renaissance derived compositions, yet they are marked by psychological density rather than serene detachment. Figures twist under chromatic pressure. Flesh is modeled with intensity rather than ideal smoothness. The body becomes a site of tension poised between historical memory and present instability. In series such as New Mythology, Tobreluts reframes classical narrative structures as analogies for contemporary experience. Myth ceases to function as distant allegory and becomes instead a vocabulary for reading rupture, endurance, and transformation. The classical body is neither celebrated uncritically nor dismantled outright. It is held in suspension, examined for its capacity to bear new meanings.

Olga Tobreluts

Russian, b. 1970

Modernization II

2002 (printed 2012)

Kodak Metallic print

47.2 × 55.1 in.

119.9 × 140 cm

Olga Tobreluts

Russian, b. 1970

Modernization I

2002 (printed 2012)

Kodak Metallic print

47.2 × 55.1 in.

119.9 × 140 cm

Ivan Plusch

Effect 5

2011

Acrylic on canvas

51 × 78 in.

If Tobreluts reconstructs the classical body through digital mediation and painterly myth, Ivan Plusch approaches it through entropy. Trained in monumental painting at the Stieglitz State Academy in St. Petersburg, Plusch engages figuration as something perpetually on the verge of disappearance. His canvases are marked by viscosity, atmospheric blur, and controlled dissolution. Figures emerge and recede within spatial fields that seem to erode them. In works such as Effect 5, the human form is present yet unstable. Paint drips are not incidental gestures but calibrated disruptions. The environment often appears more structurally resolved than the body itself, reversing the classical hierarchy in which the figure anchors space. Here, space destabilizes the figure. Architecture and atmosphere absorb it. The ideal dissolves into material process.

Ivan Plusch

Effect 1

2011

Acrylic on canvas

51 × 78 in.

This inversion carries profound implications. In the classical tradition, the body functioned as guarantor of proportion and order. In Plusch’s work, it becomes fragile, permeable, subject to time. The surface of the canvas stages a drama of persistence and erosion. The body flickers between legibility and abstraction, refusing to settle into heroic posture. Plusch’s installations extend this logic into three-dimensional space. In projects such as The Process of Passing, architectural forms are presented in states of visible decay. Monumentality is neither restored nor mocked; it is allowed to deteriorate. The viewer encounters grandeur as residue. Time becomes structural. His engagement with glass, particularly within international exhibition contexts such as Glasstress in Venice, intensifies this inquiry. Glass occupies a paradoxical position: solid yet fragile, transparent yet distorting. In Plusch’s hands, it becomes a medium for embodying instability. Figures cast or formed in glass appear suspended between presence and dissolution, refracting light rather than asserting mass. The classical impulse toward permanence is reimagined through material vulnerability.

Ivan Plusch

Episode 5

2011

Acrylic on canvas

58 × 58 in.

Ivan Plusch

Immortality #4

2019

Acrylic on canvas

59 × 79 in.

Both artists, though distinct in method, address a shared condition: what remains of inherited ideals when the political and cultural systems that sustained them fracture? In Western contexts, the return to figuration is often discussed in terms of market resurgence or stylistic cycles. In post-Soviet contexts, figuration carries additional layers of historical complexity. The body was not merely aesthetic; it was ideological terrain. Tobreluts’ early digital idealizations and Plusch’s dissolving figures can be understood as complementary responses to that terrain. One rebuilds the form as mediated image, exposing its constructed nature. The other subjects it to entropy, revealing its fragility. Reconstruction and residue operate as twin strategies. Their practices also intersect with broader international discourses. The late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries witnessed renewed engagement with figuration across Europe and the United States. Yet not all figurative returns are equivalent. In the case of Plusch and Tobreluts, the body is never simply reintroduced as expressive vehicle. It is interrogated as structure.

Olga Tobreluts

Diva

2018

Lenticular panel

38.5 × 23.5 in.

Material intelligence undergirds this interrogation. Tobreluts’ migration from early digital rendering to oil painting reflects not a stylistic shift but a sustained investigation into mediation. The brush becomes a translator of screen logic into pigment. Surfaces retain a clarity that acknowledges technological origins even as they reassert painterly tradition.Plusch’s handling of paint is equally deliberate. Drips and blurs are choreographed. Viscosity becomes metaphor for time. His glass works push this inquiry further, embedding fragility into form. The body is neither carved in stone nor sealed in bronze; it is suspended within matter that threatens to fracture. For collectors, this material rigor matters. These are not decorative quotations of classical style but sustained engagements with art history’s structural language. The works hold visual presence while operating conceptually at depth. They reward prolonged viewing. They participate in international conversations that extend beyond regional boundaries. For museums, the pairing offers curatorial resonance. Post-Soviet aesthetics, digital history, monumental painting traditions, glass as contemporary medium, and classical discourse intersect within their practices. Exhibitions that address figuration after ideology, the body in transitional societies, or the transformation of myth in contemporary art would find in their dialogue a rich point of entry.

Ivan Plusch

Immortality #3

2018

Acrylic on canvas

59 × 79 in.

Olga Tobreluts

Nimfa

2018

Stereo-Vario

Master edition 1 of 3, copy 10

40-inch diameter

At a time when geopolitical instability once again foregrounds questions of identity, territory, and cultural memory, the classical body reemerges not as static relic but as contested form. It can no longer function as uncomplicated symbol of harmony. It bears the imprint of collapse and reconstruction. In presenting Ivan Plusch and Olga Tobreluts in dialogue, Matney Gallery situates itself within a broader international inquiry into figuration after empire. This is not an appeal to nostalgia, nor a retreat into academic citation. It is an acknowledgment that the languages inherited from antiquity remain active but altered. The classical body persists. It mutates. It absorbs rupture and carries forward transformed. In the work of Plusch and Tobreluts, it stands neither triumphant nor destroyed, but recalibrated an unstable yet enduring structure through which contemporary experience continues to be measured.