Judith McWillie: Art, Activism, and the Vernacular South

Judith McWillie is a multifaceted artist, educator, and activist whose career bridges fine art, folk traditions, and social justice. Born in 1946 in Memphis, Tennessee, McWillie came of age amid the civil rights era and developed a lifelong passion for African American vernacular art. Over five decades, she has distinguished herself as a painter, photographer, curator, and professor, all while championing the cultural expressions of the African American South. Her story weaves together rigorous academic inquiry and grass-roots artistic advocacy, making her a compelling figure in contemporary art and cultural history.

Early Life and Education

Growing up in the American South informed McWillie’s worldview and creative path. She pursued formal art training, earning a BFA from Memphis State University and an MFA from The Ohio State University. This academic foundation gave her technical skill and art historical grounding, but equally influential were her encounters with Southern folk creativity beyond the classroom. By the late 1960s, while still a student, McWillie had already begun documenting the “Black Atlantic” artistic traditions in her community – an early sign of the hybrid scholarly-artistic approach that would define her career. These formative experiences laid the groundwork for her dual identity as both an artist and an art historian. In 1974, at just 28 years old, she joined the faculty of the University of Georgia’s Lamar Dodd School of Art, planting roots in Athens, Georgia that would enable her to both practice art and engage with the rich vernacular culture of the region.

Academic Career and Teaching

McWillie spent over 35 years at the University of Georgia (UGA), ultimately retiring as Professor Emerita of Drawing and Painting in 2010. As a young faculty member in the 1970s, she immersed herself in both studio teaching and field research, reflecting her belief that art education should connect to broader cultural contexts. She led study-abroad programs, such as UGA’s Cortona, Italy program in the 1970s and trips to Cuba in the 2000s, exposing students to art beyond U.S. borders. Within UGA, she rose to lead the Drawing and Painting department (serving as Chair from 1998–2005) and mentored generations of students in finding their artistic voice. Colleagues recall that McWillie’s classes were as likely to discuss the visionary yard displays of a self-taught Southern artist as the compositions of Renaissance masters – a reflection of her inclusive approach to art history. Her influence extended outside the classroom through public talks and panels; for example, she was an outspoken participant in discussions on challenges facing minority and multicultural artists in the American art scene in the late 1980s.

Crucially, McWillie’s scholarship did not stay confined to academia – she wrote extensively for a wider art audience. She contributed essays to prominent arts journals and magazines, including Artforum and Metropolis, and to influential anthologies on Southern and African American art. For instance, she penned chapters in Testimony: Vernacular Art from the African American South and Keep Your Head to the Sky: Interpreting African American Homeground, publications that explored Black folk creativity and sense of place. She also contributed to The Art of William Edmondson, examining the work of the Tennessee sculptor who was the first African American artist to have a solo show at MoMA, and to Dixie Debates: Perspectives on Southern Cultures. Through these writings, McWillie helped shape academic and public discourse, insisting that the artistry of unsung Southerners be seen as central to American cultural history. Her role as a scholar-educator earned her recognition such as a Ford Foundation Fellowship at the Center for the Study of Southern Culture in 1986, and in 2007 the James Mooney Award from the Southern Anthropological Society for her co-authored book – honors that underscore the impact of her research and writing.

Artistic Practice: Themes and Media

Judith McWillie

Holy Volt, 2010

Acrylic on canvas, 96 × 144 in. (243.8 × 365.8 cm)

“Holy Volt” (mixed-media painting by Judith McWillie) exemplifies the artist’s integration of cosmic motifs and vibrant abstraction. McWillie’s own art practice spans painting, photography, and video, often drawing on the spiritual and natural themes that fascinate her. In her early painting series, she experimented with vivid color and layered symbolism, influenced both by formal training and by the visionary environments she studied in folk communities. A piece like Holy Volt radiates with swirling celestial forms and charged hues, reflecting an imaginative cosmology that parallels the mystic creativity of the self-taught artists she admired. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, McWillie continued to explore the crossroads of the earthly and the transcendent: for example, she created a painted construction titled The Body is the Crossroads for an exhibition in Italy, suggesting an interplay of body, landscape, and spirit.

In recent years McWillie’s artwork has turned its gaze skyward. Her most recent bodies of work focus on paintings and photographs of the night sky, capturing the stars and heavens as an artistic subject. These night-sky series blend scientific curiosity with a sense of wonder, perhaps echoing the cosmological overtones she encountered in African American yard art. Indeed, McWillie’s dual identity as artist and documentarian means her creative projects often inform one another. While she has photographed vernacular art environments in daylight, her own canvases chart a more metaphorical cosmos at night. Critics have noted a meditative quality in her night photographs and paintings – an attempt to visualize the sublime, endless “waters above waters below” (to borrow the title of one of her works) that connect human existence to the universe.

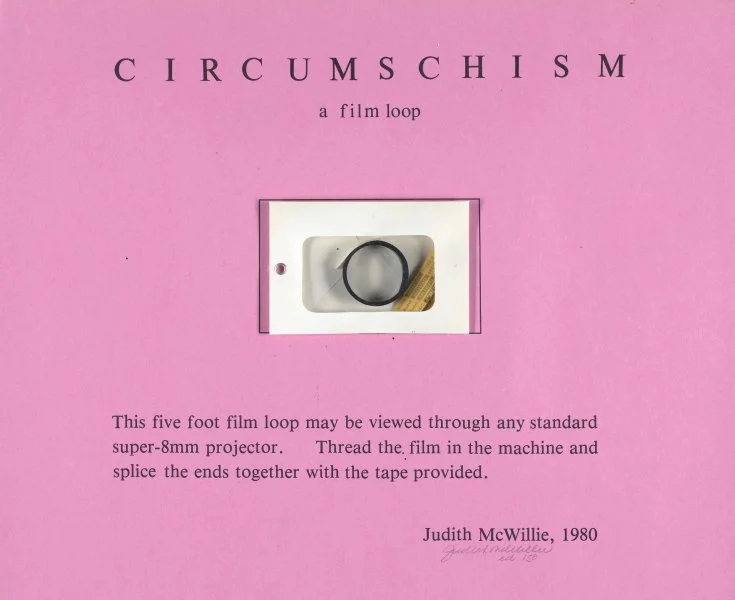

Though conceptually rich, McWillie’s art is also formally accomplished. Her paintings and photographs have been exhibited widely throughout the United States and Europe, and as far afield as Japan, Italy, and Sweden. She embraces a variety of media – from traditional oil and acrylic painting to Super-8 film and digital video. Notably, McWillie contributed an artist’s film piece titled Circumschism (1981) to the renowned portfolio Artifacts at the End of a Decade, an experimental compilation that included works by Laurie Anderson, Sol LeWitt, and others. This inclusion placed McWillie in dialogue with cutting-edge contemporaries and landed her work in prestigious permanent collections. Today, her art can be found in the holdings of major museums such as the Museum of Modern Art (New York), the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Walker Art Center, and the Harvard University Fogg Museum, among many others. These collections acquired McWillie’s works (often via the Artifacts portfolio) in the 1980s, recognizing the significance of her contributions to late-20th-century art. In addition, a dozen of her paintings reside at her alma mater in Memphis, and public institutions from London to Tokyo hold examples of her prints. Such broad representation attests to the visual and conceptual strength of McWillie’s oeuvre, even though she has spent much of her career away from the commercial art market’s limelight.

Advocacy and Vernacular Art Activism

A defining thread through McWillie’s life is her activism on behalf of marginalized art and artists, especially those from African American and Southern grassroots backgrounds. While building her own art career, McWillie simultaneously took on the role of documentarian and advocate for vernacular creativity. Much of her work – creative, curatorial, and scholarly – has focused on African American self-taught artists, whom she has sought to honor and bring into the wider art historical narrative. As an art historian, she conducted extensive fieldwork: traveling backroads, interviewing folk artists, filming their processes, and recording the cultural contexts of their work. This effort began early; by the 1980s she had amassed hours of videotape interviews with artists like Dilmus Hall, Mary T. Smith, J.B. Murray, Lonnie Holley, and others. McWillie donated a large collection of these recordings and slides to the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art and to the Southern Folklife Collection at UNC Chapel Hill, preserving an invaluable audiovisual record of African American vernacular art and its makers. This archival impulse is itself a form of activism: a commitment to ensure that these artists’ voices and visions are not “hidden” or lost to history.

In 1989, McWillie’s advocacy culminated in a groundbreaking exhibition she co-curated in New York: Another Face of the Diamond: Pathways Through the Black Atlantic South. Organized at INTAR Gallery, this show highlighted spiritual and artistic connections across African diaspora traditions in the U.S. South. It brought yard shows, improvised altars, and other folk expressions into a gallery setting, challenging audiences (and the art establishment) to value these creations aesthetically rather than dismissing them as mere ethnographic curiosities. McWillie’s research for Another Face of the Diamond was deeply informed by her field encounters, and she collaborated with scholars like Robert Farris Thompson and practitioners of Yoruba-derived spirituality to frame the exhibition’s narrative. In reflecting on her work, McWillie noted the delicate balance in presenting such material: “Decades ago, even before the question of whether or not such works could be called ‘outsider art’ emerged, some people in the art world were arguing about whether they should mainly be regarded ethnographically or if they could – and should – be discussed and appreciated aesthetically.” By curating exhibitions and writing essays, McWillie strove to help the people who make the art have a hand in constructing the context that values it, bridging the gap between academic interpretation and artists’ own intentions.

McWillie’s most celebrated scholarly contribution to this cause is the book No Space Hidden: The Spirit of African American Yard Work, which she co-authored with anthropologist Grey Gundaker. Published in 2005 by University of Tennessee Press, No Space Hidden delves into the elaborate yard environments created by Black artists across the South – from bottle trees and “sacred trash” assemblages to topiary gardens – interpreting them as profound artistic and spiritual practices. The book was widely praised for its insightful analysis and rich documentation, and it earned the James Mooney Prize, a top honor in Southern anthropology. Gundaker and McWillie’s combined perspective (anthropology and art) made the case that these yards are “rambling altars, places where spirits can be summoned and communed with,” rooted in African aesthetic lineage and adapted to the New World. In interviews, McWillie has recalled how encountering these powerful vernacular environments transformed her own understanding of art. “While I was teaching at the university, I began doing my own research about certain vernacular art forms I encountered in the South, of which African-American yard art was by far one of the most interesting and powerful,” she reflected. This passion fueled her to write, photograph, and lecture about artists like Reverend George Kornegay, whose Alabama yard became a “New Jerusalem” of found-object sculptures and painted sermons. McWillie even snapped photographs of Kornegay’s work in the 1990s that are now themselves historical documents – a testament to her role as both witness and storyteller for these creators.

Beyond the gallery and page, McWillie’s activism has extended directly into communities. One striking example is her work with the St. Paul Spiritual Holy Temple in Memphis, an awe-inspiring “yard show” and sacred site built by the late healer Washington “Doc” Harris. Locally mischaracterized for decades as a spooky “voodoo village,” the temple faced vandalism and neglect. McWillie, a Memphis native and longtime friend of the Harris family, has worked to preserve and re-contextualize the Temple’s true story. She authored a detailed narrative for the SPACES archives project, illuminating the Temple as an “essential chapter in American religious history and vernacular art,” and as of 2019 was editing a book on the site. She even helped initiate fundraising efforts to restore its monumental wooden sculptures and ritual structures, blending cultural preservation with social justice (in this case, correcting racist myths that had long stigmatized the site). In Athens, Georgia, McWillie also conceived Beloved Land (2016), a two-hour collaborative art event held at a former plantation to honor the souls of Native Americans, enslaved people, and convict laborers buried there. Part libation ceremony, part multimedia installation (with music, poetry, and McWillie’s paintings on display), Beloved Landexemplified how she uses art as a means of restorative justice – literally giving voice and visibility to those erased in official histories. McWillie acted as project director and artist, partnering with local Black activists (Knowa and Mokah Johnson), musicians, and poets to create a healing space. The event brought together diverse audiences to confront painful pasts through creative ritual, embodying McWillie’s belief in art as an agent of community acknowledgment and change.

Through these endeavors, Judith McWillie has positioned herself at the nexus of art and activism. She is often described as a “cultural worker” in the truest sense: someone who not only produces culture through her own art, but also labors to uplift and preserve the culture of others. Her advocacy has helped many Southern Black vernacular artists gain recognition in museums and scholarship. In turn, those vernacular traditions have deeply influenced McWillie’s perspective on what art can be – expansive, communal, rooted in place and spirit. As she once suggested, the “hidden” spaces of yard art are not really empty or marginal at all, but are “points of contact with the world of the dead” and with ancestry, carrying meaning for the living. It’s a vision of art as something alive, integrated with daily life and identity, which McWillie has long championed.

Exhibitions, Publications, and Legacy

Judith McWillie’s career has been marked by both creative achievement and critical acclaim. As an artist, she has participated in exhibitions across multiple continents, from solo shows in Georgia and Tennessee to group exhibitions in Italy, Sweden, and France. Her work was showcased in the 1984 Rome exhibition USA Volti del Sud (The Face of the South) and in Inside Out (Malmö Konsthall, 1986), signaling international interest in contemporary Southern artists. At home, the Georgia Museum of Art and Athens’ Lyndon House Arts Center have featured her paintings and photographs, including recent displays of her Celestial Bodies series (2024) that capture starlit Southern nights. Critics often note the lyrical and contemplative quality of her art, which stands on its own merits even as it dialogically engages with folk themes.

McWillie’s publications and curatorial projects likewise leave a lasting impact. The Another Face of the Diamond catalog (1989) and No Space Hidden (2005) remain key references for scholars of African American vernacular art, bridging gaps between art history, anthropology, and Africana studies. Her essays in journals and edited volumes have broadened understanding of artists like Sam Doyle (a Gullah painter from St. Helena Island) and traced the spiritual symbolism in Southern Black yard decorations. Because of such contributions, McWillie is frequently cited in subsequent research on “outsider” or self-taught artists; for instance, the influential Souls Grown Deep foundation’s initiatives and museum acquisitions (bringing artists like Thornton Dial and the Gee’s Bend quilters into major art museums) were part of a climate of recognition that McWillie and her peers helped create.

In recognition of her dual excellence in creation and research, McWillie has garnered respect from both academic and art communities. As a professor emeritus at UGA, she continues to be a resource and inspiration – in 2017 she was honored as WUGA Radio’s “Artist in Residence,” where an open-house at her art-filled home (itself something of a living gallery) quickly sold out. At that event, fellow art historian Janice Simon lauded McWillie’s career, highlighting how her paintings “of the night sky” and her photographs reflect an artist deeply attuned to worlds seen and unseen. Indeed, McWillie’s “unique home” in Athens, brimming with artworks and artifacts, mirrors her unique role in the art world: a space where mainstream and margins meet, where formal art and folk art co-exist and inform one another.

As of 2025, Judith McWillie remains active in writing and creative projects. She is reportedly completing a manuscript on the St. Paul Spiritual Holy Temple’s art and meaning, which promises to be yet another important document of African American cultural heritage. Her legacy, however, is already secure. It lives on in the many archives, museums, and collections that now preserve the once “hidden” arts she helped illuminate. It lives on in the students and artists she mentored during her decades at UGA, some of whom have taken up similar interdisciplinary paths in art and community engagement. And it lives on every time a viewer encounters one of her own artworks – whether marveling at a cosmic skyscape on canvas or watching a grainy video interview she filmed in a folk artist’s yard – and comes away with a broadened sense of what art encompasses. In a field often segmented by highbrow and lowbrow distinctions, McWillie’s career is a testament to bridging worlds. As an artist, scholar, and activist, she has proven that art can be a powerful form of storytelling and healing, and that the gallery wall is only one of many stages on which cultural truth can be spoken. Her work continues to inspire an art world that is, slowly but surely, expanding its vision to include the vibrant tapestry of voices Judith McWillie has spent a lifetime amplifying.