The Task That Is the Toil REVISITED: Curatorial Vision and Conceptual Framing

In August 2021, as the world staggered out of quarantine shadows, the Linda Matney Gallery in Williamsburg offered a gathering that felt less like an exhibition than a threshold. The Task That Is the Toil, curated by John Lee Matney, was conceived not as a direct chronicle of the pandemic but as a meditation on what it means to descend and return — to enter darkness and then climb, haltingly, back toward air.

The title itself, lifted from Virgil’s Aeneid by way of Jung, set the tone: facilis descensus Averno … sed revocare gradum superasque evadere ad auras, hoc opus, hic labor est. “Easy is the descent to Avernus; but to retrace one’s steps and emerge once more into light — that is the task, that is the toil.” The words resonate as myth and psychology, as allegory and omen: Avernus as the underworld, but also as collective ordeal, unconscious dread, or the long night of history.

Matney’s curatorial frame drew on this doubleness. The works he gathered did not illustrate catastrophe; instead, they carried its reverberations. Folklore, dreams, myth, and memory surfaced across media, allowing viewers to encounter resilience less as lesson than as atmosphere. Critic Margaret Richardson noted that the show’s very title signaled its multivalence: a layering of modes that refused the bluntness of literalism.

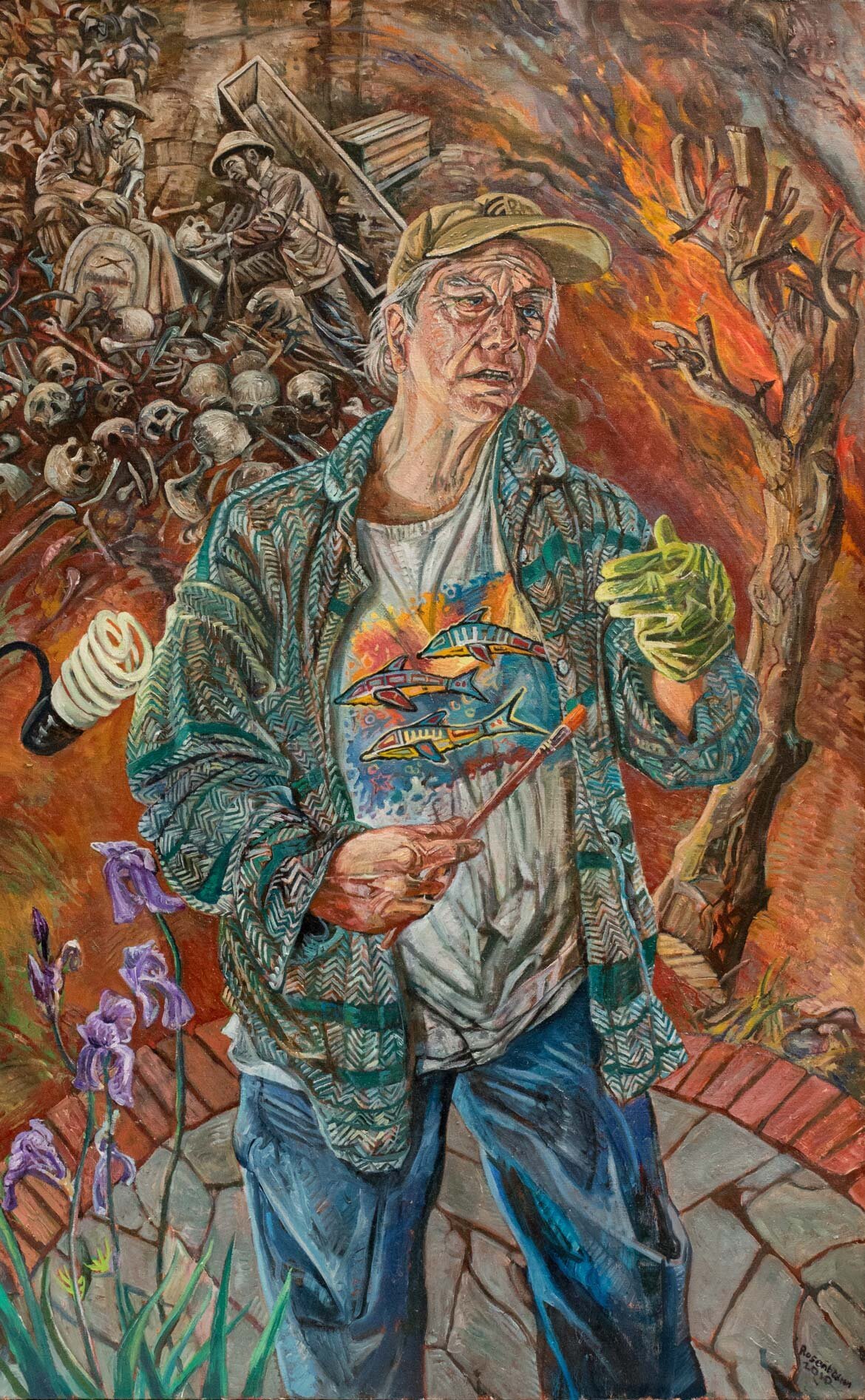

Art Rosenbaum, Self Portrait with Philippine Graveyard, 2010, Oil on canvas, 56 × 33 in, 142.2 × 83.8 cm. Jon and Christine Gilberti Legacy Collection

William & Mary students at a reception hosted by Victoria Erisman during the exhibition

Intern Victoria Erisman remarked:

“I’m very excited to be a part of the Linda Matney Gallery and to celebrate the closing of The Task That Is The Toil. This exhibition was my first introduction to the gallery’s work, and it felt like the perfect entry point. The range of pieces is eclectic yet unified by the theme Lee curated, and I admire how the show uses the pandemic as a framework without falling into the monotony of a literal approach. Talking with Lee about the art has made me a better art historian, and even in just three months, this internship has already provided me with more opportunities than I could have imagined.”

In this light, the exhibition became a chorus of crossings — each artwork a fragment of descent and return, each gesture a step in the arduous climb. Rather than situating itself only in 2021, the exhibition widened its temporal field, asking viewers to see themselves inside a pattern older than the present moment: to understand resilience as a ritual, a task forever retold, forever undertaken.

Iris Wu 吴靖昕, Untitled(spilled wax), 2020, Gelatin Silver Print, 10 × 8 in, 25.4 × 20.3 cm, Editions 1-5 of 5 + 1AP

Southern Storytelling with a Global Perspective

While the exhibition’s themes were universal, its character was deeply informed by Matney’s Southern background and cosmopolitan reach. John Lee Matney is a Virginia native who began his art career in the vibrant college town of Athens, Georgia—a 1980s–90s hotbed of progressive art and music. This dual identity (Southern roots, internationally aware) shaped the show’s curatorial mix. Nearly half of the twenty-plus participating artists have ties to Athens or the University of Georgia, and many others hail from Virginia or the American South. That Southern storytelling ethos—with its gothic imagery, historical burden, and folk influences—was a strong undercurrent. At the same time, Matney expanded the scope to include artists from Chicago, New York, California, France, Brazil, China, and beyond. The result was a dialogue between regional narrative and global context. As Margaret Richardson noted, Matney has an affinity for Southern-connected artists; however, the scope of the gallery is increasingly national and international, and the exhibition reflected that breadth.

Eliot Dudik , Matthew Grason, 7th South Carolina Died, 256 Times, Archival Pigment Print, 32 x40 in

One way this integration manifested was through subject matter: Southern historical memory met universal myth. Rather than anchoring that memory in a monumental statesman, Matney turned inward to a figure from his own creative lineage—Jeremy Ayers—through his photographic diptych Shards (1994/2021). In the diptych, Ayers meets the viewer’s gaze with calm intensity while holding a lapel pin of his mother as a child, stitching together personal and cultural memory. Re-edited in 2021, the piece’s very title signals fracture and reassembly; Shards becomes a meditation on how images—and lives—are broken and remade, embodying the exhibition’s Virgilian labor of descent and return. Hung nearby was photographer Eliot Dudik’s Matthew Grason, 7th South Carolina Died, 256 Times (2013–15), a haunting color photograph of a Civil War reenactor lying on the ground in Confederate uniform. The young man’s bright eyes stare straight upward from the earth—he has “died” hundreds of times in mock battles, re-living a defeat that is not truly his yet embedded in his heritage. The pairing of Matney’s Shards and Dudik’s photograph created a conversation about legacy and liminality: where Shards models a hard-won emergence into light—an image retrieved from the underworld of the archive and returned transformed—Dudik’s fallen figure is caught in cyclical underworlds of repetition and reenactment. It is a stark meditation on how the Southern past, with its traumas and ghosts, continues to linger and haunt (a theme echoed elsewhere in the show).

Ryan Lytle, In the Shadows, Installation

Scott Belville, Reunited, 2019, Oil on panel, 27 × 24 in, 68.6 × 61 cm.

At the same time, international and cross-cultural references enriched the storytelling. A striking example was Ryan Lytle’s installation In the Shadows (2011/2021), which draws on Japanese folklore to tell a tale of shapeshifting and uncertain identity. Installed in a small room painted a vivid, otherworldly blue, Lytle’s life-sized sculpture of a kitsune (fox spirit) mid-transformation into a human became an immersive fable of liminality. In Japanese myth, fox spirits can be tricksters or guardians, and Lytle’s piece played on that ambiguity: visitors peered in to see a furry fox figure with neon-pink eyes and 3D-printed teeth, while on the wall behind it a painted shadow of a man rose up like smoke, cast by the creature. This merging of Eastern legend with the show’s broader psychological theme underscored that the “feelings of in-betweenness” were not bound to one culture.

Indeed, throughout The Task That Is the Toil, Southern gothic met global mythologies. Christian and Classical imagery mingled with African American vernacular traditions, and personal dreams intersected with ancient archetypes. Such diversity was intentional. As Matney’s roster showed, the artists included not only local storytellers but also those with perspectives from Latin America (Brazilian-born participants), East Asia (including photographer Iris Wu), and other far-flung influences. This created a rich tapestry wherein, as one reviewer put it, “myths, folklore, and dreams are represented” side by side—whether it’s Adam and Eve cast out of Eden in a Southern painter’s hands, or a Shinto fox spirit rendered in felt.

Untitled (peeing in the snow), 2020, Archival Pigment Print, 20x24”, Edition of 5 +1AP

William Ruller, Gore, 2020 Oil, Clay on Canvas, 32 × 24 in