Polychromatic Daydream , 2009 Acrylic, spray paint and ink on Yupo paper 10 × 20 in

Ani Hoover: Accumulations of Memory and Material

Ani Hoover is an artist who has built an entire language from the overlooked. Recycled yarn, plastic bags, cereal boxes, bicycle inner tubes, even her own earlier paintings become her raw material. Through cutting, knotting, weaving, crocheting, and sewing, Hoover reshapes what others discard into sculptural forms that are vivid, tactile, and unexpectedly monumental. Her work invites us to reconsider what art can be: not something distant or precious, but something rooted in the fabric of daily life, reimagined with care and imagination.

Astro-dot-net, 2010

Cut pieces of painting (acrylic and spray paint on Yupo paper) and zip ties

From Painting to Found Material

Hoover began her career as a painter, trained in the formal traditions of abstraction. In 2008, she produced a monumental series of six works on paper for an exhibition titled Up, Down, Around. Each painting measured 30 feet by 5 feet, spanning entire walls like scrolls. The works captured transitions from top to bottom, creating an immersive field of gesture and color. The effort was enormous—both emotionally and financially—and when the show concluded, Hoover felt exhausted and uncertain of her next step.

The turning point came in her studio, looking at a stack of unfinished paintings stored beneath a table. Rather than reworking them, she began cutting them apart, using the fragments as collage material. Tied together with zip ties, the cut paper became the foundation for a new series. One of these works, Astro Dot Net (2010), would come to represent a new direction: painting transformed into object, color becoming material. From there, Hoover began seeking out recycled supplies—bike tubes, plastic bottles, cereal bags—challenging herself to make art without purchasing traditional materials. She even set herself a rule: for one year, she would buy no new art supplies. This restriction, far from limiting her, became the key to unlocking a new creative path.

Hoover has described this period as liberating. Instead of approaching a blank canvas, she approached a pile of discarded matter with the question: “What could I do with this?” It was a different kind of creativity, one that redefined both her process and her philosophy.

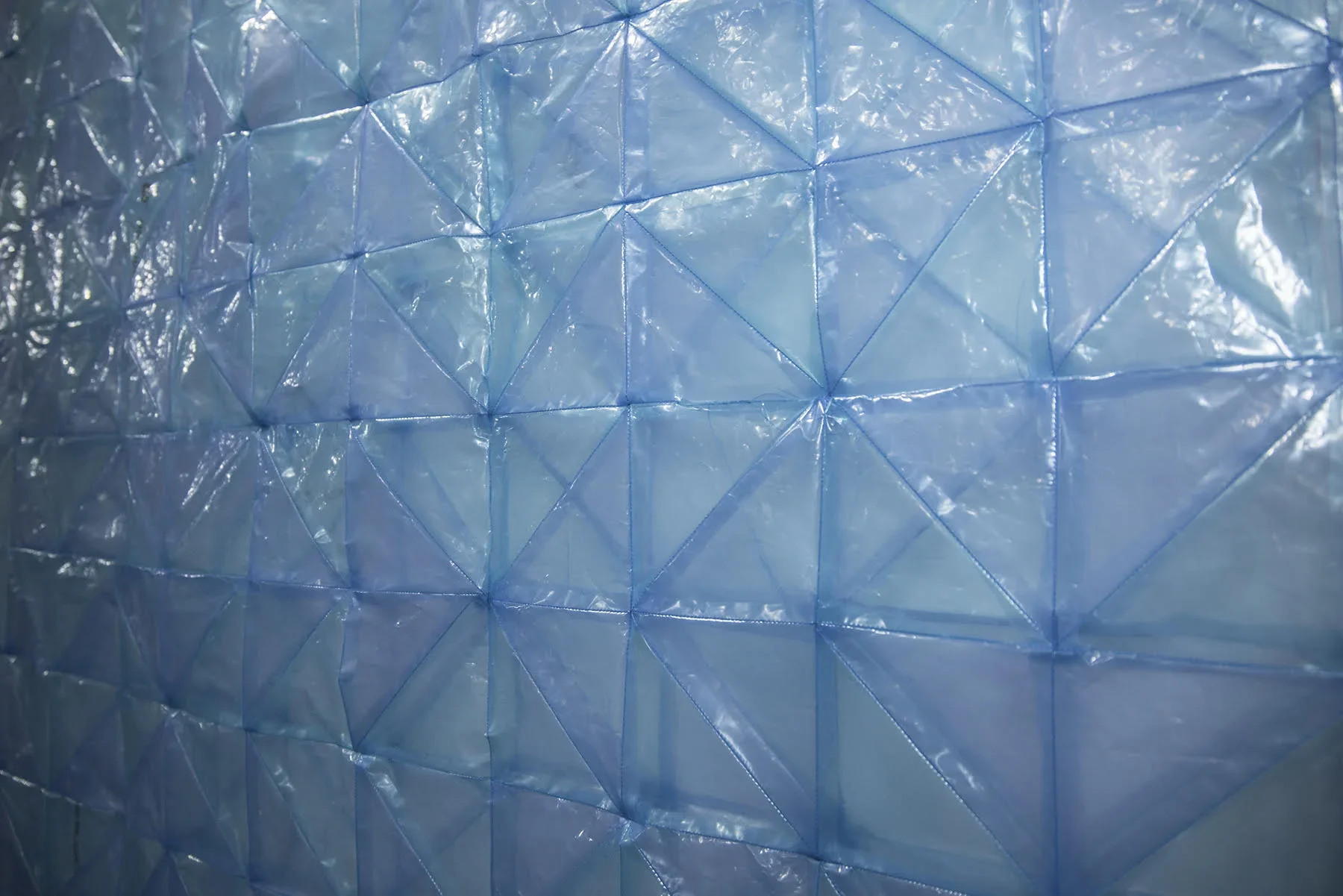

Sewn Sky, 2016

Post-consumer plastic and tread

Memory as Material

Alongside her embrace of recycled materials, Hoover turned to memory as a generative force. She asked herself a simple but profound question: “When was I happiest making art?” The answer took her back to childhood, before art school, before the pressure of being an “artist.” She recalled afternoons with her grandmother, an accomplished crocheter who filled the house with yarn, afghans, and craft magazines. She remembered summer camps, craft projects, and the sense of play that comes with making without expectation.

Big Granny, 2017

Thrifted and recycled yarn

Those memories became a foundation for works like Bloom, Potholder Sampler Wall, Sewn Sky, and Blush. Each carried forward the gestures of craft and the language of domestic making while reframing them in a contemporary context. Her Potholder Sampler Wall drew on the simple woven squares familiar from childhood craft kits, transformed through repetition into a large-scale installation. Sewn Sky and Blush used thrifted plastics and threads to recall the improvisation of handmade quilts, layered with color and texture. These works are not nostalgic, but rather a reactivation of memory—finding in the joy of craft a wellspring for contemporary abstraction.

Rubber Gardens (15x15), 2019

Post-consumer bicycle tubes in wood frame

Color and Restraint

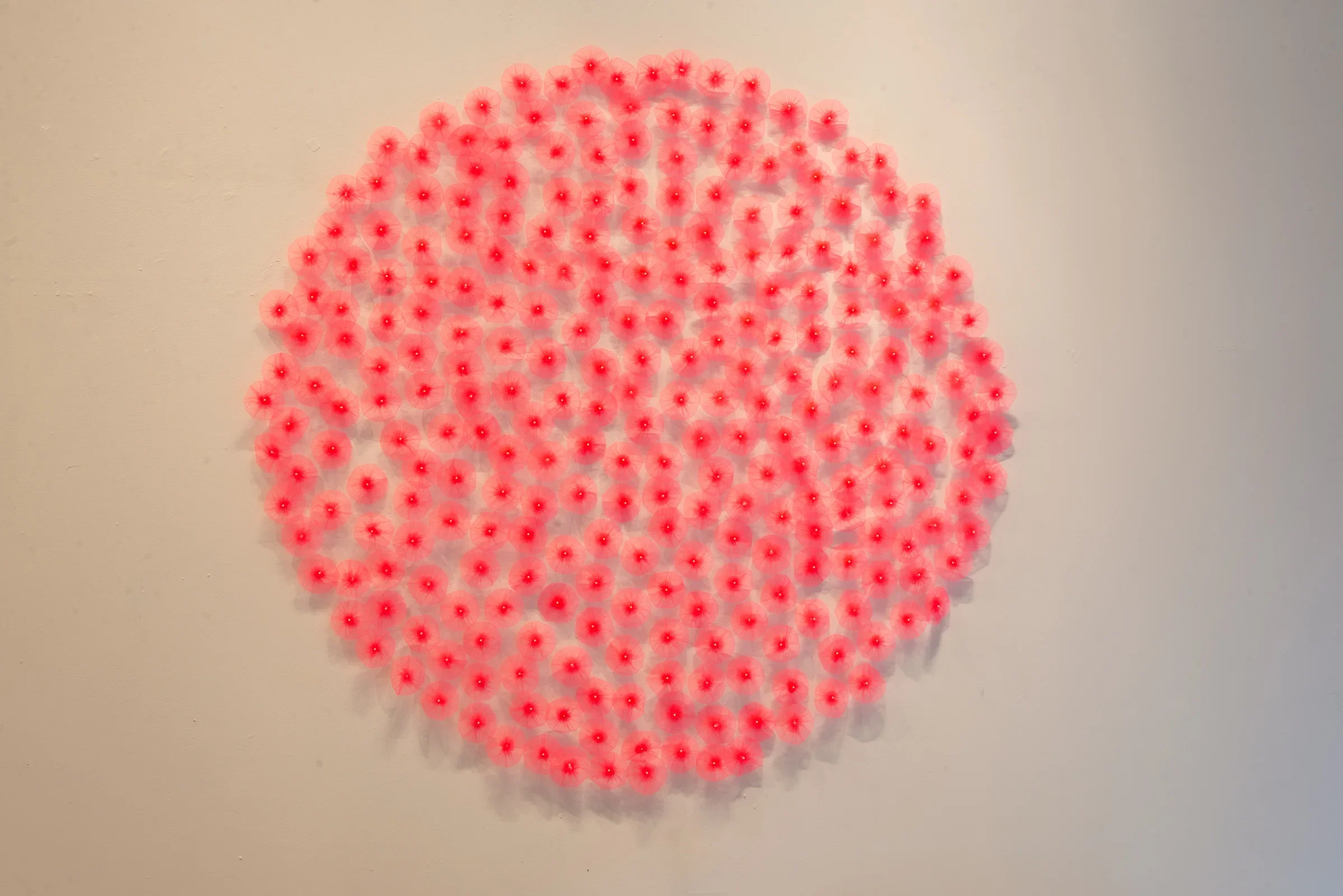

Color has remained central to Hoover’s sensibility, even as her materials have shifted. She gravitates toward light, bright hues—neon pinks, luminous whites, soft but radiant tones that hover between pastel and jewel. In some works, she uses color obliquely, allowing painted backs to glow against walls, or letting a thin thread carry the chromatic charge of a piece.

At the same time, she embraces restraint. Her Rubber Garden series, composed entirely of black bicycle tubes, rejects color altogether. These works, with their knotted and bent forms, evoke organic gardens and floral motifs, but their dark surfaces create a striking counterpoint to her more chromatic pieces. The refusal to paint or alter the tubes keeps the material honest, the flowers blooming in their own stubborn blackness.

This interplay—between exuberant color and stark restraint—underscores Hoover’s command of visual language. She understands that color can be loud or quiet, abundant or withheld, and that its impact is often strongest in contrast.

Accumulate at Matney Gallery

In 2019, Matney Gallery presented Accumulate: Works by Ani Hoover, a solo exhibition that brought together a decade of her practice. Hoover arrived in Williamsburg with a van packed to the brim with works spanning ten years. She did not know exactly how the show would unfold until she entered the gallery’s tall, open space. Over three days of installation, she arranged the works until they began to speak to one another: monumental canvases aligned with crocheted clusters, potholder walls faced black rubber gardens, and smaller experiments filled the interstices.

The result was an exhibition that embodied the very title Accumulate. The gallery became an environment of juxtapositions—large and small, colorful and monochrome, soft and rigid. Visitors encountered the works as a field of textures and scales, drawn into the immersive rhythms of repetition and variation.

The opening reception revealed the vibrancy of this environment, and the closing reception deepened it. Hoover returned to Williamsburg for the final week of the show, bringing her potholder looms to share with visitors. She invited the public to try making their own woven squares, bridging the distance between artist and audience, between professional art and everyday making. Conversations bloomed as easily as the crocheted flowers on the walls. In this way, Accumulate was not only an exhibition of objects but also a demonstration of Hoover’s ethos: art as a process of transformation, connection, and memory.

Local press recognized the impact of the show. Writers noted the way Hoover’s work “straddles the line between fine and folk art,” capturing both the rigor of abstraction and the warmth of handcraft. For many viewers, the exhibition offered a fresh way of seeing the ordinary—not as disposable, but as material with potential.

Recognition and Collections

Hoover’s work has been widely exhibited and is included in significant collections, such as the Albright-Knox Art Gallery and the Burchfield Penney Art Center. She has been collected by institutions and private collectors across the country, affirming both the seriousness and the accessibility of her practice.

Her inclusion in these collections situates her within broader currents of contemporary art: the renewed attention to fiber and craft, the emphasis on sustainability and reuse, and the dialogue between fine art and vernacular traditions. Hoover’s practice resonates with these conversations while remaining deeply personal, rooted in her own memories and material discoveries.

Art as Renewal

At its core, Hoover’s work is about renewal—of materials, of memory, of vision. She takes what is overlooked and gives it new shape, accumulating fragments into wholes that are greater than their parts. Each piece carries the story of its making: the cut of a former painting, the knot of a rubber tube, the weave of a potholder loom. Yet together they form a body of work that is both contemporary and timeless, rigorous and joyful. Her art reminds us that making need not begin with rarity or perfection. It can begin with what is at hand—with scraps, remnants, and memories—and through imagination, it can become something extraordinary.

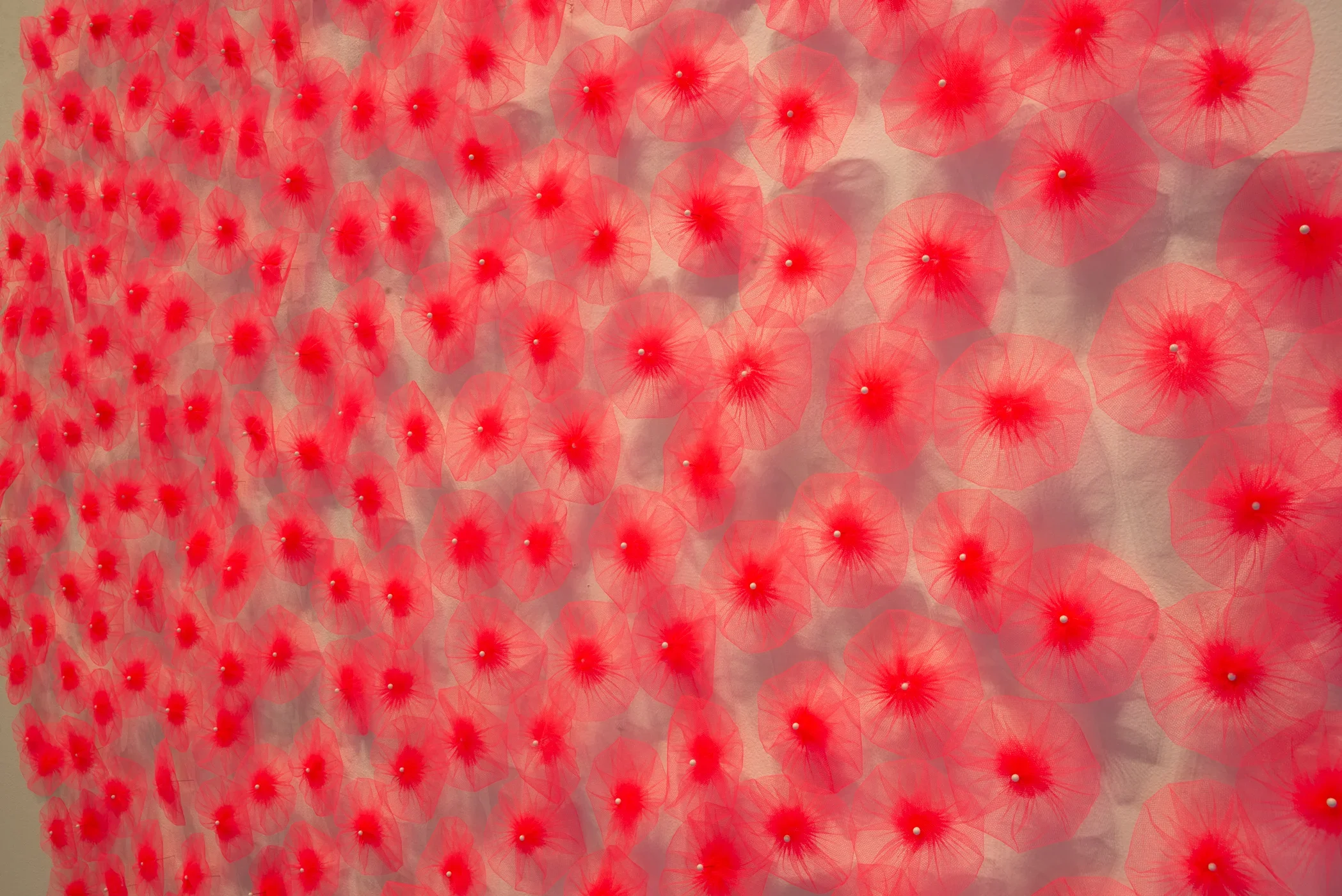

Bloom, 2016-2019

Tulle, thread and straight pins