Profile on William Ruller

William Ruller’s work carries the weight of lived history and the fragility of human impact on the land. Raised in upstate New York in the shadow of abandoned tanneries and poisoned streams, he translates that memory into paintings that are both elegiac and unsettling. His practice, rooted in clay and oil, places decay, reclamation, and the precarious balance between collapse and renewal into vivid dialogue.

Ruller’s surfaces are haunted by ruins—barns, mills, and industrial relics—yet his palette insists on life. Bright, searing reds and acidic greens press against weathered tones of gray and blue, staging a tension between memory and immediacy, permanence and erosion. What emerges is not only a personal vocabulary of tone and texture, but also a larger meditation on how environments absorb human intervention and ultimately outlast us.

In conversation, Ruller situates his canvases within this broader horizon: a discourse on time, mortality, and the inevitable reclamation of the man-made by nature. His work insists on that razor’s-edge moment—between collapse and continuation—where painting, like the land itself, is never fixed but always becoming.

Book II

Oil, Clay Encrusted Book

43 x 60cm

2012-2025

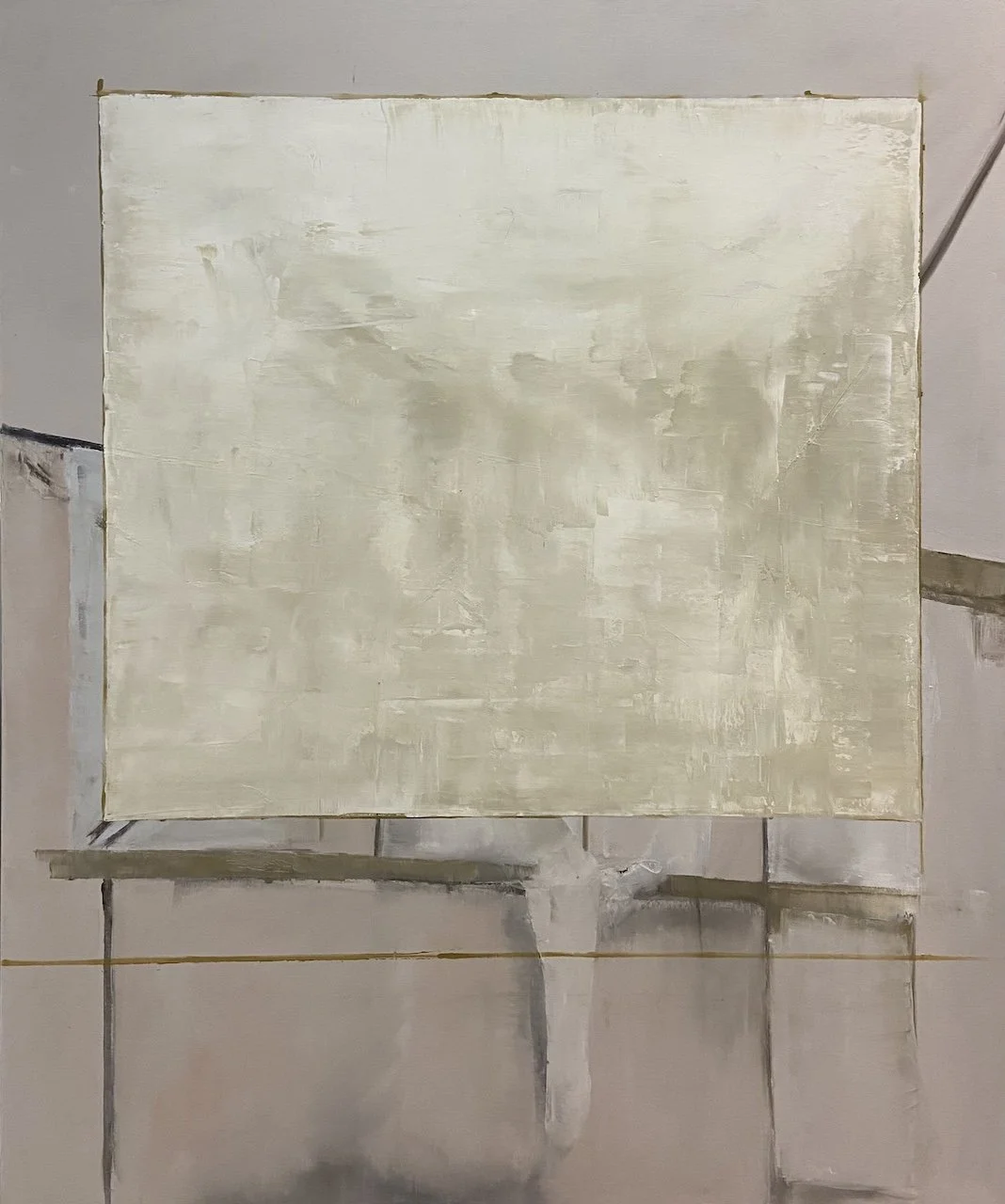

Good Morning Captain

Oil on Canvas

120 x 100cm

2022

Landscapes of Disintegration

The point of departure is biographical and material at once. Ruller grew up in Gloversville, New York, a town historically defined by leather tanneries whose waste contaminated soils and waterways. In the early 2000s, federal and state agencies began remediation programs, removing arsenic- and petroleum-contaminated soils and capping chromium residues. Those archives read like an index of the very hues that recur in Ruller’s paintings: the caustic greens of dye runoff, the iron-rich reds and browns of oxidized metal, the gray of exhausted concrete.

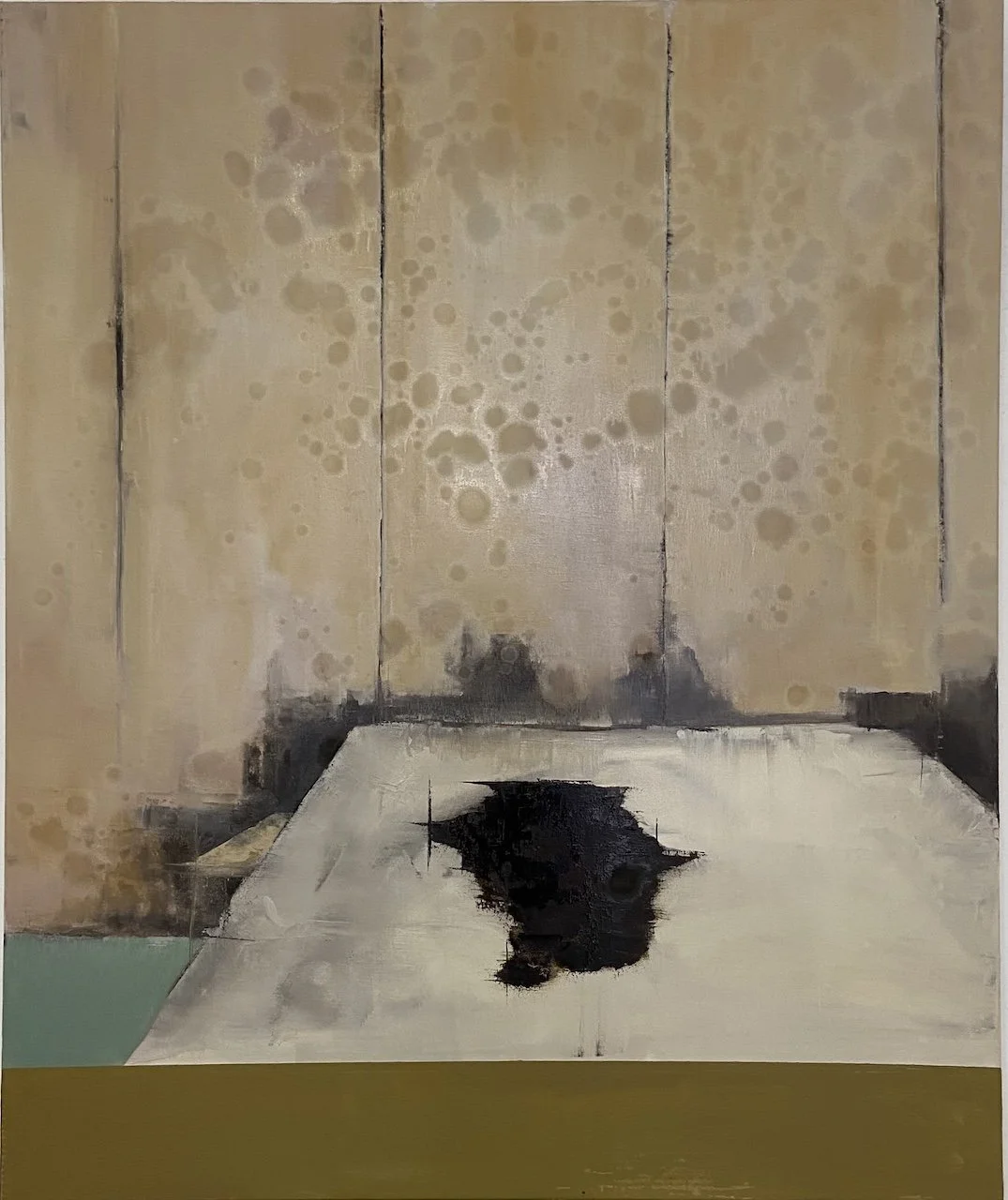

Miller II

Oil on Paper

130cm x 280cm

2022

For Ruller, these are not journalistic subjects so much as embedded memories. He recalls swimming as a child in a stream that ran near a mill, then photographing those condemned interiors as an adult—acidic puddles, collapsing passageways—so the “feel” of those spaces could be worked back into his surfaces. The paintings don’t illustrate a site; they carry forward its atmosphere: the smell of clay and rust, the sensation that the ground itself is unstable, the sense that time is peeling everything away.

When he thinks about disaster, he often frames it at the moment just before or just after collapse—the urgent threshold when disintegration hasn’t yet erased the evidence of what stood. He has described choosing works that hold a “Chernobyl-like” charge: not a literal depiction, but that specific tension where everything is still legible and already disappearing.

The Jungian Edge

Ruller’s interest in Jung is not decorative. He wants paintings to occupy the liminal zone between waking and dream, populated by symbols that are present but not resolved. The paintings hover there voluntarily, sitting on the knife-edge where the work can either cohere or fall apart. Many painters know this state—a moment of vertigo when skill and certainty recede and a different, riskier logic has to carry the piece forward. Ruller courts this edge and sometimes stops there, ending a painting precisely at the point where interpretation remains open and the image feels “half-dreamed.”

Untitled (Interior)

Oil on Canvas

150 x 120cm

2025

Color, Tone, and Memory

Although he increasingly pits hot color against earth and ash, Ruller insists he is “a tone person” more than a colorist. He often begins with “obnoxious” reds, yellows, and pinks—too bright, too alive—and then muddies them down as the work proceeds, the way a barn’s painted red fades after seasons in weather. Occasionally he flips the script entirely, forcing himself into discomfort by pairing a slab of unmuted, saturated color with his habitual tonal field—the diptych as a self-set trap he must work his way out of. The result is an internal theatre: color that threatens to overwhelm, and form that refuses to yield.

That aesthetic tension has been called the “toxic sublime”—images whose beauty entangles with evidence of contamination. It’s an apt frame for Ruller’s seductive yet troubling chroma.

In the Late Day

Oil on Canvas

120 x 100cm

2024

Materials Beyond the Canvas

Ruller’s training in ceramics keeps his practice anchored in touch. Clay—earth itself—moves into his paintings and into small, hand-held book-objects meant to be touched and smelled. He builds micro-ecosystems where painting is one element among others: branches, found objects, ceramic skins. The strategy connects, not by imitation but by affinity, to artists who have asked materials to carry memory and history as content. Anselm Kiefer’s use of lead, straw, and plant matter in heavy, time-scarred surfaces is one example; Julian Schnabel’s plate paintings, another, where fracture and accretion themselves become the image.

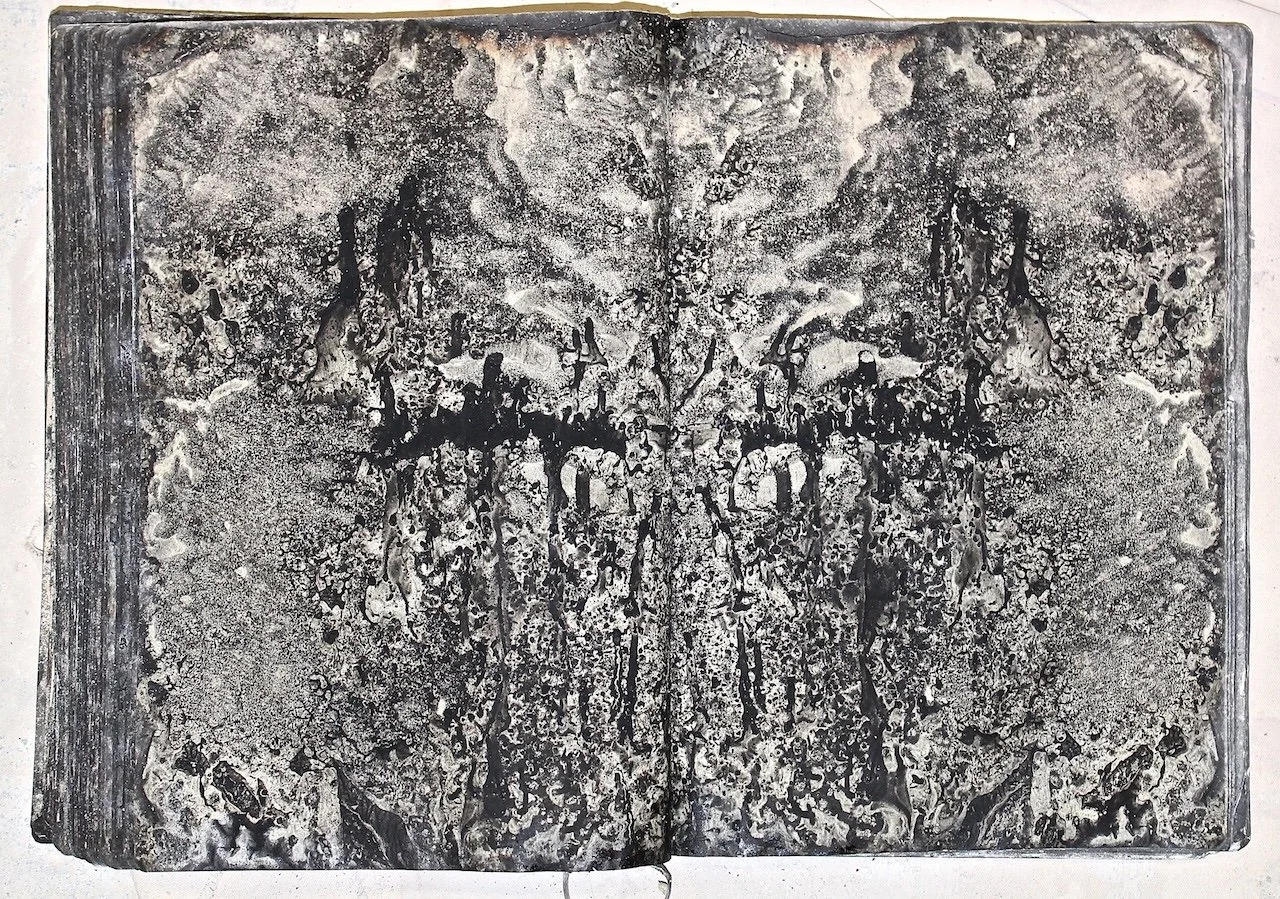

Book I

Oil, Clay Encrusted Book

43 x 60cm

2012-2025

Process, Rule-Breaking, and the Map That Must Be Rebuilt

Ruller speaks of process in terms many painters will recognize: mapping, destroying, rebuilding. Works may begin as legible landscapes before being dismantled and remade—scraped, muddied, layered—until representation loosens and another structure asserts itself. The lineage to Richard Diebenkorn runs through this cycle of building and undoing, a learned willingness to sacrifice the “finished” for the work that might exist on the other side of risk.

That risk extends to composition: edges that misbehave, bands that don’t resolve, forms that refuse to sit politely. At times Ruller deliberately introduces a problem—too much color, an element out of place—to see how far he can bend the logic of the image before it snaps. He compares it to juggling: once you can manage three, you add a fourth; eventually you change the objects—orange to knife—to keep the practice alive.

In Here We Are All Anemic

Oil on Canvas

120 x 100cm

2024

Ruins in Reverse and the Anthropocene Lens

When Ruller looks at collapsing malls or abandoned mills, he is not only seeing material; he is seeing time. The American ruin is fast, almost indecently so. Structures built within living memory rot in on themselves, while elsewhere in Europe—a Roman bridge he passes daily in the south of France—structures pre-date entire nations and remain in use. The paradox is historical, but it is also conceptual. Robert Smithson famously wrote of “ruins in reverse”: suburban construction that seems to rise into ruin even as it is built. The phrase helps name the temporal dislocation Ruller paints: the feeling that collapse is built in from the start.

Contemporary discourse offers another frame: the Anthropocene, a proposed epoch in which humans act as a geologic force. Whether embraced or contested, the Anthropocene vocabulary has altered how museums and artists read images of extraction, waste, and degraded landscapes. Ruller’s canvases are not merely “about” a place; they sit inside this larger cultural reckoning with human-altered terrains.

Photography has been central to that reckoning. Edward Burtynsky’s long project on industrial and “manufactured” landscapes—mines, quarries, tailings ponds, oil fields—has shaped how audiences see the scale and allure of extraction. While Ruller’s medium and method differ, both practices wrestle with the double bind of beauty and harm, and both ask how an image can hold critique without sacrificing formal power.

Gallery View

Installation, Immersion, and the Viewer’s Body

Ruller doesn’t only paint; he stages encounters. In exhibitions, he often brings clay-covered book-objects, small sculptures, and found fragments into proximity with the paintings, nudging viewers to move, to handle, to smell. The strategy shares a family resemblance with immersive installation practices that manipulate space and sensation, though Ruller aims for a quieter intimacy. Consider Mike Nelson’s labyrinthine environments, which unsettle orientation and produce an embodied, psychological response; Ruller’s scale is smaller, but the underlying question rhymes: how can an environment alter perception and keep the viewer present?

The Razor’s Edge, Revisited

Over and over, Ruller returns to thresholds. A painting that could still fail is more alive than one that is merely resolved. The moment before collapse—the instant when a dark field begins to shed its heaviness or when a block of hot color starts to harmonize with the mud beside it—is the moment he wants to preserve. He has spoken of “calling a painting finished” precisely when the risk remains visible, when the form still carries the tremor of uncertainty.

That choice has aesthetic consequences. It’s why his circles can read as moons marking time across a bleak horizon, or as chemical halos hovering over a poisoned field. It’s why a slab of candy-apple red may pulse like a wound or a warning flare. It’s why a minimal diptych can feel, paradoxically, maximal in implication.

Silence I (Huile, Argile sur Toile) (2020)

Works, Titles, and Touchpoints

Specific works clarify the breadth of this language. Silence I (Huile, Argile sur Toile) (2020) compresses the tonal and the tactile into a modest rectangle: oil and clay on canvas, a field that reads as both scarred ground and unsettled sky. Gore(2020) pushes further into bodily color, letting the material thickening of oil-and-clay deliver a visceral charge plainly implied by the title. Smaller works on paper—Bluefield studies among them—show how pared-down formats can still carry the same dialectic of mood and matter, memory and mark.

Ruller’s comments about these pieces often point back to childhood color memory—the barn red that’s already faded, the water that shouldn’t be that shade of green—and forward to a painterly ethics of risk: if the painting feels too easy, it isn’t done; if it feels impossible, it might be close.

Gore (2020)

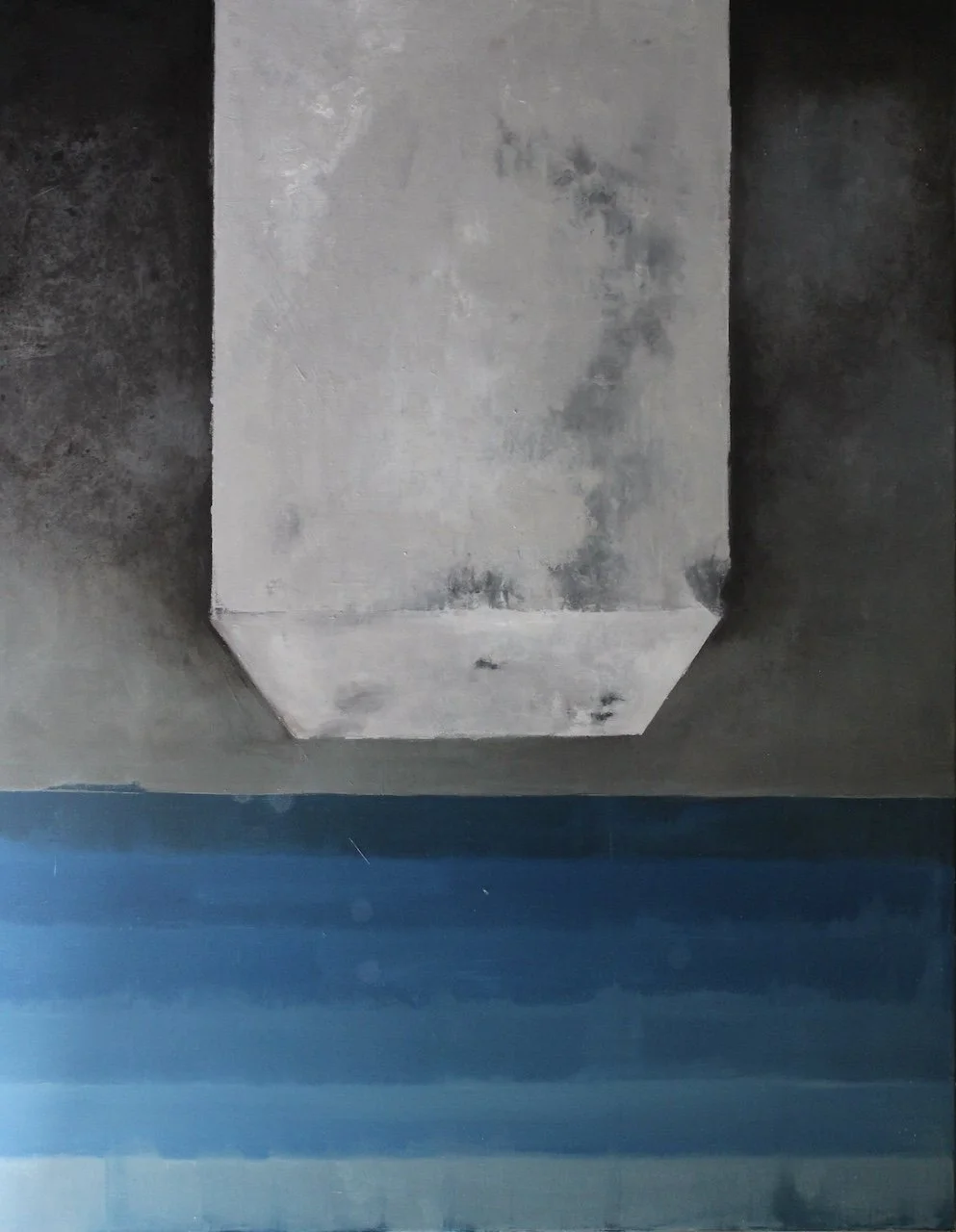

Untitled (Lg. Blue)

Oil on Canvas

150 x 120cm

2025

Why This Matters Now

Institutions are actively reframing landscape as a site of politics, care, and contested histories; recent shows in the U.S. and U.K. have expanded the field far beyond pastoral scenes to include protest, ecology, and the aesthetics of extraction. That curatorial current aligns squarely with Ruller’s project, which pairs a grounded regional memory (upstate industrial ruin) with transatlantic questions of time and endurance (Roman infrastructures still in use). For museums, the work offers an articulate, sensory entry point into Anthropocene-era display, where material speaks as forcefully as image. For collectors, it offers durable, painterly objects that carry cultural relevance without sacrificing the pleasures of surface, touch, and craft.

Because Ruller’s practice is materially rigorous yet conceptually legible, it can sit across departments: contemporary painting, material/installation, environment-focused initiatives, or regional history projects that connect American post-industrial narratives to global conversations. The clay components and book-objects open installation possibilities beyond the wall, while the paintings themselves—especially the newer diptychs—offer formal anchors for thematic groupings on memory, ruin, and repair.

Untitled (Tanning Drum)

Oil on Canvas

150 x 120cm

2025

Time, Ruins, and the Human Condition

Ruller’s insistence on paradox—every breath as both life and loss; every image as both building and unbuilding—gives the work its philosophical spine. The paintings keep instability visible without theatrics. They show how a ruin begins long before a building falls, and how reclamation can proceed quietly, almost imperceptibly, as new forms of life take root in contaminated soil. Standing before these works, one senses not nostalgia but comprehension: a clear-eyed acknowledgment that our landscapes are repositories of our choices, and that those choices are written in color, tone, and texture—sometimes beautifully, often indelibly. The canvases don’t solve anything; they teach us how to look when looking is difficult. That, finally, is their claim on us. They return us to the very edge they inhabit: the moment between collapse and continuation, where attention itself becomes a practice of care.

Sources for context

On Gloversville tannery contamination and remediation (EPA/NYDEC/NIOSH summaries). Ext Apps+1CDCGloversville Business

Jennifer Peeples’s concept of the “toxic sublime.” DigitalCommons@USU

Robert Smithson’s “ruins in reverse,” from A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic. holtsmithsonfoundation.org

Anselm Kiefer’s materials and themes (lead, straw; history and memory). The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Julian Schnabel’s plate paintings. The Guggenheim Museums and Foundation

Richard Diebenkorn and the Ocean Park process/series. Whitney Museum

Edward Burtynsky and The Great Acceleration (ICP, 2025). International Center of PhotographyThe Guardian

Curatorial reframings of landscape (Tate Liverpool’s Radical Landscapes).

William Ruller’s Studio

The Corner

Oil on Canvas

120 x 180cm

2022

Gallery view

Book III

Clay, Photo Transfer in Book

43 x 60cm

2012-2025

To Those Before

Oil on Canvas

120 x 100cm

2024

Untitled (Lg. Block)

Oil on Canvas

150 x 20cm

2025