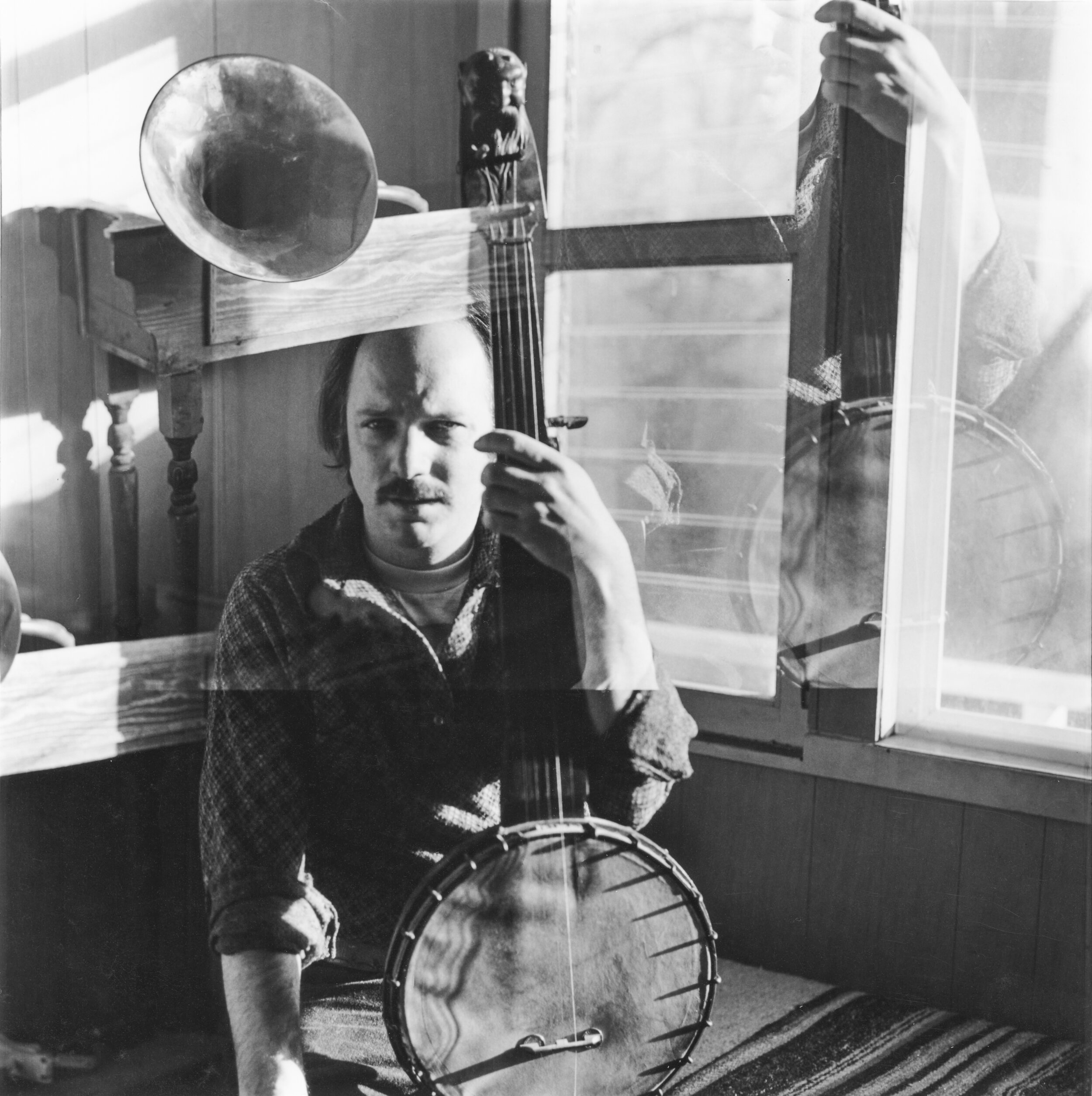

Kent Knowles in the studio

SOUTHERN GROOVE: KENT KNOWLES REFLECTS ON ART ROSENBAUM, PART 1

“Sometimes a painting will catch your eye from a distance and hook the viewer by the rib cage,” wrote Jeff Maisey of Veer Magazine. I know the feeling well—Kent Knowles’s work has had that effect on me for years.

Kent, a longtime Matney Gallery artist and professor at SCAD Atlanta, has spent over two decades developing a distinct visual language grounded in narrative, gesture, and psychological nuance. In this conversation, we revisit his time as a graduate student at the University of Georgia and explore the formative influence of his mentor, Art Rosenbaum—an artist, folklorist, and central figure in the Southern figurative tradition.

What emerges is not only a portrait of artistic lineage, but a reflection on how the ethos of Rosenbaum’s practice continues to inform Knowles’s approach to painting today. This is Part 1 of an ongoing dialogue examining the intersections of regional legacy, studio practice, and contemporary figuration

Hi Kent, great to see you. First I'd like to ask you to talk about paintings by Rosenbaum that resonated with you as a student, and today's a mid-career artist,

Hey Lee, thanks so much for having me—it's really great to be here and to speak with everyone. I also want to thank you for giving me this opportunity. It’s exciting for me because I had the chance to study with Art Rosenbaum and to see how both his work and mine have evolved over the years. What’s especially meaningful is that I knew him as my professor at the University of Georgia, where I was in the MFA program from 2003 to 2006. It’s a three-year program, by the way—I didn’t stretch it out, it’s just built that way! One of the great things about it was that we had the opportunity to teach while continuing our own studies

Art Rosenbaum in his studio with artist Tyrus Lytton

And so, when I think about Art Rosenbaum, he was really the first person I got to meet. I don’t know if you all are familiar with the graduate program at Georgia—it’s pretty exclusive, if I do say so myself—and they offer some wonderful scholarship opportunities. Naturally, I was hoping for one of those scholarships. I happened to be in the area, and after I applied, Art Rosenbaum reached out and said, “Hey, want to come check the place out?” Of course, I said yes. I honestly wasn’t expecting to meet with Professor Rosenbaum himself. I thought maybe an administrative assistant would greet me and point toward the art building. But it turned out to be quite different. I met with Art directly, and that completely blew me away. I’d seen his work and heard about him, but I wasn’t quite prepared to actually be sitting in his office. And what an office it was—like something out of a movie. If a set designer were told to create the quintessential art professor’s office, that would’ve been it. There was a skeleton, tons of books, and, of course, Art himself—brilliant, warm, and engaged. I remember a great Pontormo poster on the wall. Pontormo was an Italian mannerist, and he’s one of my all-time favorites.

Art Rosenbaum in his studio, Athens, Georgia, 2017

I remember sitting down in that dusty chair and thinking, Oh man, I’m in the right place. And of course, Rosenbaum delivered. He took me around, and it was a fantastic experience—you just get this feeling like, this is where I belong. I felt that almost immediately, and it was such a pleasure. Over the years, I got to know him better and work with him, but that Pontormo poster in his office really stuck with me. The mannerist style—it resonated. I think that’s something Art does so well: he brings a lyrical quality to painting, especially in his figures. That’s a good word—lyrical. As you probably know, the Mannerists came after the Renaissance. By that point, artists had already figured out how the body worked—they knew the anatomy, the structure. So the question became, what next? They started using the figure not just to depict, but to express—to push the emotive potential of the human form. I always felt like that was right in line with what Art was doing.

Art Rosenbaum, Rakestraw's Dream, 1993, Oil on linen, 78 x 106 in.

I was thinking, which one should I talk about? This one, this one, does all the talking; Rakestraw’s Dream

I think this is a quintessential Rosenbaum, and what I think many people don't get right off is just how complex his compositions are. it's one thing to say, Hey, I'm going to have six figures in a painting but to be able to direct the viewer's eye from one spot to the next and to maintain a focal point and to do all of that it's not just a matter of scale or contrast. Still, you have to deal with temperature and color; You can't have everything hot at once because the viewer's not going to know where to look. And then anytime there are any symbols or text that triggers something else in the human eye that says, Oh, I need to read this first.

or I need to pay attention to this object first. I know I'm probably talking to some art people out there, so I don't mean to simplify things, but to be able to orchestrate a multi-figure, multi-surface giant canvas is no easy feat. And I think one of the best takeaways I had from working with Rosenbaum is that they would sneak up on you. The paintings would sneak up on you. So would you'd say, Oh yeah, that painting with the guy grabbing the guitar on the water. And somebody else would say, no, no, it's that painting with that shirtless guy, holding that figure., no, no, it's not. It's the one with the window, you know? There'd be such an over-saturation of information, but yet it would be so well composed that I would liken it to an excellent film. You, you don't just experience the film and then walk away; it kind of haunts you, and maybe two days later, you're still thinking about it. For me, it has always been a strength of Rosenbaum's work because it resonates with you, and I think this painting is no exception. Another thing I got from, Rosenbaum, was not just color.

But his ability to draw, because he did this equally] well, just with limited palette or limited materials. I really appreciated his work because he would oscillate between these grand paintings and these drawings. However, to maintain that type of focus still with these complex compositions, I always pulled something from that. So I really liked that he gave all of his students this green light, to be ambitious with what they do, but then to also, you know, jump around with media and see what comes out of that exploration.

Art Rosenbaum, The Studio and the Sea II, 2015, Charcoal and conte, 30 × 44 in,

KK: He was a pretty intense character. I don’t know how many of you had the chance to hang out with him, but he still has a very vigorous studio practice—just as he did 15 years ago when I first knew him. He could be an intimidating figure in a way. He was extremely accomplished. Even before you worked with him, you’d feel a little hesitant. But he was quiet about his accomplishments—you don’t often meet someone so humble about what they do. He never wore it on his sleeve. The more you talked with him, the more you’d discover—like, Oh, you speak French? Oh, okay... and another language?Wait, what do you mean you just got a Grammy? I regret never having the courage to join in the sea shanties he would host at the Gobe. I was kind of in that group. I think overall, it was his love for everything going on around him, while still being able to give his energy to so many different things. He’d pull out some music or tell you stories about the great days in New York and his art collection. He really sets the bar high.

Art Rosenbaum, Untitled Diptych, 2014, Casein, 60 × 80 in. Available. VIEW ON ARTSY

Art Rosenbaum, Strainer, Oil on linen, 140″ x 84″, 2008

Art Rosenbaum, Howard Finster with Couple and Fire, 2006, Oil on canvas,

JLM: Comment on the legacy of figurative painting at UGA

KK: In a way, it’s really a great time to be an artist right now. I think it’s probably a great time to be anything right now. A lot of the instruction we’ve had up until now—granted, we’re living in a post-postmodern arts climate—still draws on ideas rooted in Modernism, where you'd have people hanging out together, writing manifestos, talking about what they wanted to accomplish as a group. That kind of communal artmaking has splintered in recent times, because people are now globally connected. Still, even so, you see a form of that. Take Instagram, for example. You see a forum—whether shaped by the algorithm or just your own interests—where you start to curate what you want to be surrounded with. That’s not unlike, for me, finding a solid group of artists to smoke cigarettes with, drink coffee, and talk about conceptual development. What we have now is a version of that, but it’s worldwide. I could be looking at an amazing painter from Switzerland and seeing real similarities. You see this in film, in scientific discovery—pretty much everything—where there’s something out there in the ether. Multiple people are addressing it at once. It feels current, but it’s also shared. (Synchronous discovery.) At the same time, you don’t want to deny the potency of regional influence—whether you're going to a place specifically to study with someone or to absorb something from a particular geography. That kind of influence is real. But I’m more interested in the things that creep out from under the floorboards. I can say, at least during my time at Georgia, there was a slant toward figurative work. And I don’t mean it was orchestrated—it just happened. It was fascinating. We had Art Rosenbaum, of course. Then Scott Belville, a figurative painter. And Jim Herbert—an abstract figurative painter. He was interesting, too. He’d paint nude, and these were 12-foot paintings he’d be hand-painting.

Art Rosenbaum, Jim Herbert, 1984, Oil on linen, 50 × 42 in, 127 × 106.7 cm. VIEW ON ARTSY

(It was a) pretty amazing time, but a lot of it centered around physicality. If you look at moments in history, you can start to see—at least in retrospect—a correlation between how artists behaved and the state of technology or whatever was happening in the world. Things were getting kind of slick in the early 2000s—we had smartphones, giant screen TVs. For the area I was in and the people I was around, there was a real nod to acknowledging the human body. It showed up in the form of figuration—synchronicity. I’ll take it.

Art Rosenbaum, Self Portrait with Camera, 2001, Oil on linen, 52 × 46 in, 132.1 × 116.8 cm, VIEW

I love the South. I love being an artist in the South because I still feel like the rest of the world doesn’t quite understand what’s going on here. There’s that Southern mystique—which could be said of other places too—but there’s something very elemental about certain parts of the world. Maybe it’s the oppressive heat, maybe it’s the landscape, maybe it’s the home of cicadas. There’s something really grand about the South. I think it’s probably going to be perpetually misunderstood—because, politics aside, there’s just something about the region. And when I say “the South,” I mean anything south of D.C.

Kent Knowles, The Iron Triangle, Oil on linen, 66″ x 72″, 1994, private collection

JLM: Can you talk about a few of your works and how they intersect the Rosenbaum?

KK: One of the things I took from Rosenbaum was this unabashed, almost ribbon-like quality in the figure—his ability to twist forms so they fit within a composition and respond to their environment. It didn’t fully hit me at the time, and I don’t know how you all process things, but for me, it takes a while for certain lessons to really resonate and sink in. So I was part of the experience, immersed in it, and it felt a lot like discovering things about myself—figuring things out through paint. It was shortly after graduate school that I started to see those influences surface, especially in the way the figure was intentionally distorted and in my growing attention to pattern. Go back to that first image—what a curveball. You’ve got patterns on the tie, the pattern of the water, reflections on the glass and the rocks, the wrinkles in the fabric. All of that is a great challenge. It’s like giving a chef 15 ingredients and saying, “No, you can’t just pick three—you have to use them all. But if you overpower the dish, you’ve failed.”

Kent Knowles, Alto, Oil on canvas, 48x60 in, 2013, Private Collection

KK: I always loved Rosenbaum because there was this unabashed quality to his work. You have to have a strong stomach to engage in that kind of activity. While my own work is nowhere near as complex as his, I always felt that his paintings were a visual representation of the complexity of his mind. To go from French to music to teaching to painting—you see the equivalent of that in the visuals he created. Of course, I’m still trying to marry these interesting, somewhat mysterious narratives. In his paintings, there’s music happening, but there’s also something else—like young romance, or man and nature. There’s even a sense of God in there.

Kent Knowles, Urchin, Oil on canvas, 72 x74 in, 2013

I remember saying, all right, I'm going to make some big surfaces, and I'm going to try to make them as complex as possible. Still, I wasn't very good at gravity, so I ended I ended up putting a lot of paintings underwater, so that, so that if the gravity wasn't quite what Rosenbaum would do, at least I had this, this kind of life preserver, pun intended, uh, to keep me, keep me composing without having to deal with gravity. But it was fun being a student too.it was a wild ride

JLM: What are some paintings that have defined the trajectory of your career?

Kent Knowles, Bloom

KK: Bloom was a pretty big one for me. I started realizing that, that I wanted these mighty girls navigating space. This was the first one, but they increasingly became in this state of danger; there was this sense of peril, and it was something that kind of surprised me. I have other images I could show you, but like there would be a painting of a girl climbing up a tree and sawing off the branches as she made her way up. I was thinking, wow, that's very self-destructive, but unlike Rosenbaum, I could only focus on one kind of protagonist, if you will an the entire narrative would anchor around that figure

Kent Knowles, Undoing

I always marveled at Rosenbaum’s paintings because he could do multiple things within a painting yet still maintain a focal point, which is not easy. In a way, his paintings remind me of a Giotto sequential fresco where one thing happens and another and another, but you're experiencing it all at once. I think it's a real testament to not only his way of designing surfaces but also to our neuro-plasticity, our ability as a human race to develop and process information, multiple bits of information all at once. So in that way, I think he's kind of ahead of his time because you have to catch up to him, not the other way around.

JLM: Urchin was in on our show Art House on City Square in downtown Williamsburg, a collaboration with the city in 2013. And this was the year after we did Substrata Tyrus Lytton. For this piece, I saw your process going on and I saw how you changed it in different ways. I really think that's exciting when you're changing something as you go, and you're using your cell phone, and you show me one version, and then another version which kind of evolved into this one. Can you discuss this piece?

KK: Sure. So you know what, so a lot of people will see a painting of mine, and again, I can't speak about Rosenbaum's work because I, I think even if he explained to us what he was doing, it'd still be a mystery., and say you decided to paint a painting of a person holding a sea urchin, surrounded by an octopus. Yet, nothing could be further from the truth. In fact, the narrative always takes a back seat. It's not even acknowledged or even thought out until there's a design. This really started as it is just a series of lines that overlap and collide until a form starts to present itself. When it does, I have the wonderful privilege of figuring out how to nurture that idea and still make sure it works somewhat logically in a composition. The first underwater painting I ever did was because I had a figure that looked like they were floating, but I couldn't figure out why. I didn't want them to just be floating, although I let myself do that later.

JLM: Well I definitely see that. You are both masters of color and dynamic movement.

KK: Well, I appreciate that you know, um, and when I see his paintings, I think music, you know, as I think about, and I, I don't, I don't write music, but I know that there has to be like a crescendo. Then there has to be, you know, some rhythm that occurs over and over, and then there's some refrain, or again, I don't know music terms, but when I see his work, I think music, um, and I would love for people to, you know, have that feeling in my work too.

JLM: What are some other milestone works for your career?

KK: They're still coming along. Um, I did, there is one painting, um, and I couldn't find it regrettably, I couldn't find an image. Cause as I said, I'm a horrible, uh, documentary, but I did a painting once of, um, when I was in graduate school, that's when we had Hurricane Katrina. For whatever reason, I had a very, just a profound , emotional response to that. I remember seeing the footage and just thinking how come nothing's happening? This is America, what's going on. I remember there was a, there was a gentleman, a victim of the flood who did not know how to swim and nd so he had fastened these two giant kind of igloo coolers e to his arms, like giant floaties. I was in graduate school when that was happening, and I remember what an impact it had, and I didn't know how to handle it. So I was whacking away at these two canvases. It was a diptych or just a two-part canvas, I guess you could call it a diptych, but it was really because I couldn't make them any bigger. So I just put two big ones together, and I struggled with this thing, and it just wasn't happening. And you know, it's one of those things you hear about in, in books. , it's like one of the paintings fell over for whatever reason.

Maybe I was throwing things at it; it wasn't happening, it wasn't coming together. And so I went there to put it back up, and I said, well, what if I put it on the other side and then the painting just came together. And it was an exciting moment because before I had two figures, and one was like on a little chunk of land here andnd one was on a little chunk of land over here. And between them was this great expanse, and it was new Orleans, and houses were covered in water.

You know you could only see their rooftops. There was like an old highway that had collapsed. And anyway, what happened is when I switched them, those two little landmasses, there became an Island and suddenly all the activity was happening around this little patch of dry land and the painting just came together and it wasn't until later that I realized that Rosenbalm had a similar thing.

JLM: This is The Deluge, which is in a private collection here in Virginia.

KK: My painting was called the flood

Can you discuss Island? I love the angles of the water and this one and the reflections. Is is very difficult for you to do these reflections and hash that out?

Kent Knowles, Island, Oil on canvas, 72 x74 in, 2013

No, it's not. Because we're already dealing with non-reality, that's one thing II enjoy about my work; I'm not beholding to reality, so to speak, because I don't use references. And I think these weird kinds of lobster creatures are kind of a testament to that. I start with something.- maybe there'll be a jellyfish, and then it becomes something else, and maneuverability allows for, of course, gross human distortion, but it also allows the design to come first. What's interesting about this painting is that it's this type of view; we understand it. We can see the cross-section of, of water, like the interior/exterior. We see the surface; we see below the surface that wasn't available until film and cinematography or photography came around.

So we can say, Oh yeah, that's just a cross-section. But outside of maybe scientific illustration, people wouldn't understand why. They'd say, why is that weird triangle of foam, you know, floating above the water? We have to consider that commercials and film, and music are always conditioning us to interpret space. And when a new, new image comes along after that wears off, it just becomes part of our communal understanding of space.